An introduction to Beck in 10 records

An album-by-album journey through the topsy-turvy world of Beck.

Beck Hansen – the grandson of Al Hansen, who co-founded the surrealist art collective Fluxus, and the son of musician/arranger David Campbell and former Warhol protégé Bibbe Hansen – was bound to inherit some artistic genes.

In 1993, his debut single ‘MTV Makes Me Want to Smoke Crack’ was an attention-grabbing, acoustic folk-blues stunt, as well as a specific ‘anti’ reaction to alt.rock’s prevailing grunge, hair metal and industrial trends. Then came the equally unexpected ‘Loser,’ a much more commercially slanted and hip-hop-inspired track that accidentally predicted the slacker ethic (he claimed he conceived the chorus after thinking, “I’m the worst rapper in the world”).

But Beck saw both tracks as originating from the same place, to engage audiences. Live, he tapped performance art with spontaneous, maverick diatribes and props, including a Star Wars stormtrooper mask and a leaf-blower.

If this sounds like a dilettante at work, the next 24 years have proven otherwise, with free-flowing melody, hooks and rhythms across a pop, soul, blues, hip-hop, disco, punk, funk, Tropicália, country, folk and rock. His new album, Colors, is his most pop-centric for 20 years, co-created with producer-of-the-moment Greg Kurstin (Adele, Sia, Lily Allen, The Shins), though they go back to the early Noughties, when Kurstin was Beck’s keyboardist. Loser? Hardly. Here’s ten records to show why.

Beck

Golden Feelings

(Sonic Enemy, 1993 / vinyl bootleg pictured)

Beck’s debut album title parodied 1960s MOR compilations like Golden Mellow Moments. Musically, he had the consciousness-raising beliefs of his parents’ generation in his sights, likewise the folk-blues stylings of their protest singers. Having sung Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly songs on stage, Beck composed his own lo-fi-scratchy versions, sometimes decelerating the vocals and tempo for authenticity’s sake, and playing off-key (try the dirge-a-thon ‘Trouble All My Days’).

These art-rock tactics suggested Beck didn’t envisaged a career in music, and Golden Feelings was only available on limited-edition cassette, but word soon got around. The album was only reissued on CD in 1999, making it Beck’s least-known record, but it’s one of his most fascinating (NB ‘Super Golden Black Sunchild’ is a great Donovan parody, should you be looking for it).

Beck

Stereopathic Soulmanure

(Flipside Records, 1994)

Bong Load released 500 12” copies of ‘Loser’ in 1993, even though Beck didn’t rate the track, only to see it storm radio and commence a major-label bidding war. Geffen won, but only a week before his debut Geffen album Mellow Gold (another MOR parody), and Beck was still allowed to unburden this 25-track sprawl (through Flipside).

A primitive bricolage of blues, country, skronk, psycho-babble, leaf-blower and hardcore, Stereopathic Soulmanure lead with the detuned blues-into-punk of ‘Pink Noise’, followed by the Gram Parsons-emulating country-rock sadness of ‘Rowboat. By this time, ‘Loser’ was in the US Top 40, and rose to number ten, but Beck was still evidently keen to maintain a nonchalance toward commerciality and predictability.

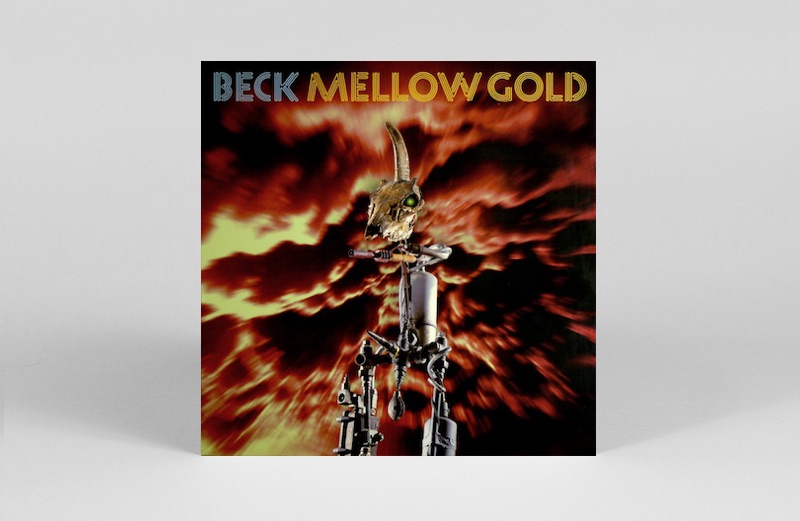

Beck

Mellow Gold

(Geffen, 1994)

Mellow Gold’s more concise, sharpened vision was rooted in sampling, “a way to break down things, to make something my own,” Beck reckoned. But the album didn’t wear its sourcing on its sleeve, as much of hip-hop did; whatever he borrowed was fit seamlessly into an eclectic vision, with as much genre-hopping (blurry ballads, choppy folk-blues) as his version of rap.

Anyone thinking they’d get more like ‘Loser’ would have been surprised by ‘Steal My Body Home’ and the seven-minute finale ‘Blackhole’, which had more in common with his first two albums’ warped frequencies. Even more followed three months later, with the 16-track One More Foot In The Grave, which turned out to be his last such DIY experimental splurge.

Beck

Odelay

(Geffen, 1996)

Having discharged a grand total of 71 tracks over four albums within two years, Beck settled into a more traditional pattern, while retaining ambition and occasional sonic hairpin turns. Odelay could have been very different. Beck begun recording a sombre, ballad-based record with Mellow Gold producers Bong Load, a.k.a. Tom Rothrock and Rob Schnapf (only ‘Ramshackle’ survived, plus two more tracks on the Odelay deluxe reissue), but instead moved on to the hip-hop-favouring Dust Brothers.

‘Hotwax’ and the chorus of ‘Where It’s At’ – “got two turntables and a microphone” – celebrated (and featured) vinyl scratching, while the record’s big hits – ‘Devils’ Haircut’, ‘The New Pollution’ and the aforementioned ‘Where It’s At’ are among the nineties’ snappiest modern-pop conceits, foraging forward while paying tribute to hip-hop’s electro roots. Odelay was album of the year across the board, and his most successful album ever (currently on its way to 2.5 million sales).

Beck

Mutations

(Geffen, 1998)

The ‘sad’ record that Beck began with Rothrock and Schnapf turned into Mutations, produced by Nigel Godrich after he’d helmed Radiohead’s OK Computer. Motivated by the fear that fans might think Beck had lost the plot, Geffen did NOT market as the official follow-up to Odelay – even though all Beck’s earlier records had included mordant ballads as part of his post-modernist agenda.

Mutations’ low-key, downbeat dreaminess – performed by humans more than computers – was gilded by acoustic guitars and occasional strings. Beck’s lyrics were more personal too, such as ‘Nobody’s Fault But My Own’. Some of his magpie-thieving stayed intact, for example the bossa-nova detour ‘Tropicalia’, perversely released as a single in the UK, and the Odelay-aping hidden track ‘Diamond Bollocks’.

Beck

Midnite Vultures

(Geffen, 1999)

As if Beck had expunged all his melancholia in one go with Mutations, his next step was to emulate Prince’s nouveau disco, on stage too (the big bed, the dance manoeuvres). A sign of Beck’s immense talent was how effortless it sounded, without help from sampling either: just a straightforward, strutting blue-eyed dance record, as focussed on one style as Beck ever got (though the aberrant ‘Beautiful Way’ could have slotted on to Mutations).

‘Sexx Laws’, ‘Midnight Bizness’ and ‘Get Real Paid’ would have lit up Studio 54 if the tracks had been around 25 years earlier, while the closing ballad ‘Debra’ remains a career highlight, a delicious and funny slice of lounge lizardry (“I wanna get with you / and your sister / I think her name’s Debra”) that sounds like an alternative universe smash for Hall & Oates.

Beck

Sea Change

(Geffen, 2002)

As if Beck had expunged all his pop tropes in one go with Midnite Vultures, he instantly swung back to Mutations’ sound and vision, (complete with Nigel Godrich). That album meant it wasn’t quite the sea change that the title suggested, but Sea Change went deeper into misery-ville, after the break-up with his long-time girlfriend in 2000.

Cue “singing from the heart”, and an album that made Mutations sound like a knees-up in comparison: no bossa-nova or pop escapades, just exquisite open-heart surgery, ballads often wrapped in strings (arranged by his dad), and none better than ‘Round The Bend’, with a lush, elegiac drift that emulated Nick Drake.

Beck

Guero

(Interscope, 2005)

As if Beck had expunged all his misery in one go with Sea Change… A new wife, and first child was a fresh start, but that said, Guero was a relative retrograde step by his standards, and featured a reunion with Odelay producers, The Dust Brothers. The past cropped up too through the word ‘guero’, Mexican slang for a pale-skinned or blonde-haired person, which Beck was often called through his East LA-based childhood among Latino communities, and the album had more of a Latino flavour than before.

‘Qué Onda Guero’ and ‘Hell Yes’ were also chips off the Odelay block, with pop-tronic bites such as ‘E Pro’, with its “nah nah nah nah” chorus (like Coldplay, Beck is a master of the chant-proof singalong hook), the sunshine-poppy ‘Girl’ and the folk-blues ‘Farewell Ride’ widening the remit. It reached number two in the US charts, though I’d venture Guero is no one’s favourite Beck album. But maybe its creator thinks otherwise, as Beck played six of its tracks on his 2016 UK tour.

Beck

The Information

(Interscope, 2006)

If Beck albums were a question on Pointless, you’d do well if you mentioned The Information. A) It features Nigel Godrich, who brought his trademark warmth and depth to a rhythm-based collaboration for once, and b) Beck’s melodic nous never seems to fail him, if ‘Think I’m In Love’ and ‘Cellphone’s Dead’ are anything to go by.

The piano-based ‘Strange Apparition’ encroaches on Elton John’s ‘California 1970’ phase, while the ten-minute triptych ‘The Horrible Fanfare/Landslide/Exoskeleton’ is a dance hybrid that anticipated LCD Soundsystem. Still, no alarms or surprises – but did anyone want Beck’s ‘Jazz Odyssey’ anyway?

Beck

Morning Phase

(Capitol, 2014)

2008’s Modern Guilt, produced by fellow retro-futurist Danger Mouse, added a late ’60s psych vibe, and two of his finest songs: the crunchy ‘Gamma Ray’, and the psych-dreamy ‘Chemtrails’. But it’s really a superficial advance, and in terms of overall construction, it was his third such record in a row – a strange place for an artist this restless.

Maybe a spinal injury – incurred during a video shoot in 2005 – was holding Beck back. It gave him the chance to slow down, re-assess and make space for multiple side projects (producing albums for Charlotte Gainsbourg, Thurston Moore and Stephen Malkmus; curating the Philip Glass remix project; three standalone singles in 2013 alone and Song Reader, a 20-song album in the form of sheet music).

When a new Beck record finally arrived, it was his first Mellow Gold in 12 years, with a gorgeous, fleshed-out, 1970s Topanga Canyon vibe. Maybe Morning Phase wasn’t fired by heartbreak, but Beck was feeling his age, and the streaming/download cultural changes affecting his musical career. There’s a believable world-weariness here, in all its analogue beauty, with ‘Morning’, ‘Wave’ (just voice and strings) and the luminescent guitar trails of ‘Waking Light’ among his best ever.

If Beck had found himself on the opposite side of pop, Colors – begun before Morning Phase, but delayed while Greg Kurstin found the time to finish it – is the about-turn for which Beck is renowned. As a purposeful let’s-have-hits gambit, Colors is expertly rendered, and fizzes with burnished choruses and crisp beats, but I don’t find it that convincing; it sounds over-worked, tweaked and procrastinated over much like the majority of 21st century pop, made by committee. Compare that to Beck’s initial splurge, and free-form view of a musical career, and you wish he’d just let go return to a more spontaneous mindset. Knowing Beck though, he might just be on that path.