“Our record shops once were oracles, temples, energy centres for all kinds of music and youth movements,” says Garth Cartwright, whose new book chronicles the diverse history of the UK record shop. From the Jewish immigrant communities of ’30s Whitechapel to Sheffield’s Warp-affiliated FON and the Stern’s West African record shop to the modern day and the enduring appeal of spots like Honest Jon’s and Spillers, David Katz joins Cartwright on a journey to discover what makes these places so special.

Where would we be without record shops? As portals to a sonic universe, they have introduced us to the soundtracks of our lives, the specialist knowledge of proprietors yielding scrolls of wax that illuminate hidden aspects of the world we inhabit. As gateways to the vestiges of shared musical experience, they have brokered countless lasting friendships and a fair few marriages too. Many outstanding British performers are intricately connected to them, including The Beatles, Shirley Bassey, Dusty Springfield and Elton John; Bowie said his teen apprenticeship at A. T. Furlong in Bromley first revealed how shiny round discs of flat black plastic could strongly affect people’s behaviour, and described working in a record shop as a vocation on par with the teaching profession. Often run by independent smallholders that are as passionate about the music they stock as their customers, record shops hold a special place in the British psyche, being crucial markers of popular culture and social interaction.

“The history of UK record shops is a great, great story — so important that it should be a source of national pride,” says Garth Cartwright, the New Zealand-born, London-based author of Going for a Song: A Chronicle of the UK Record Shop. “I can see some people thinking, ‘Say what?’ But our record shops once were oracles, temples, energy centres for all kinds of music and youth movements. The best record shops allowed for people to gather and share wisdom. You didn’t go to them just to spend money and return home with a record—no way! They were places of learning, teachers in the true Sufi sense.”

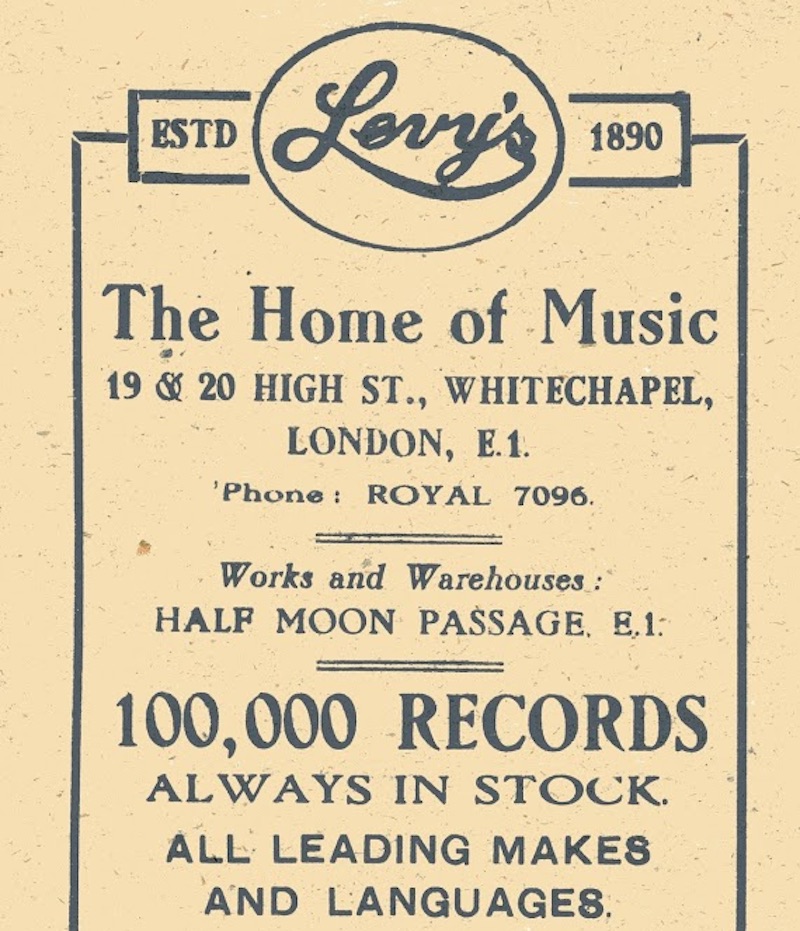

The book begins with a profile of Spillers of Cardiff, which began selling pre-recorded music on wax cylinders in 1894 and is still going strong some 124 years later. We find HMV opening on Oxford Street in 1921, Levy’s of Whitechapel servicing the East End Jewish community and visiting seamen with “100,000 records always in stock,” and Dobell’s becoming a West End haven for jazz, blues and folk from the mid-1950s, with Bob Dylan making a clandestine contribution to a Dick Farina album in its basement.

Manfred Mann’s future lead singer, Paul Jones and bluesman John Mayall have youthful music epiphanies at shops in Portsmouth and Manchester, and writers Val Wilmer and Peter Guralnik are similarly moved at The Swing Shop in Streatham. As the book progresses, there are increasingly surprising connections: picture a young Charley Harper of the UK Subs buying a Prince Buster album from a shop in the Oval after having seen him live at Brixton Town Hall, the Clash’s Paul Simonon scoring bluebeat from Desmond’s Hip City in Brixton, Brian Eno bagging Doris Duke and Steppenwolf at Musicland on Portobello Road, the Pama Brothers selling The Moody Blues along with ska at their tiny Kensal Green shopfront, and Morrissey discovering Attack releases at Paul Marsh’s in Moss Side.

“I see the best record shops not just as retailers but collaborators in creating great music, in a manner akin to how the best recording studios and producers and engineers — they help focus and shape and inspire creativity,” continues Cartwright. “And as there is no book that looks at the great record shops and the forces they unleashed—forces that helped shape music making across the 20th Century — I had to write it. From music hall and dance bands, trad and modern jazz and the early ’60s blues and mod bands through to ska and reggae, punk and disco, techno and dubstep, they’re all linked to specific record shops.”

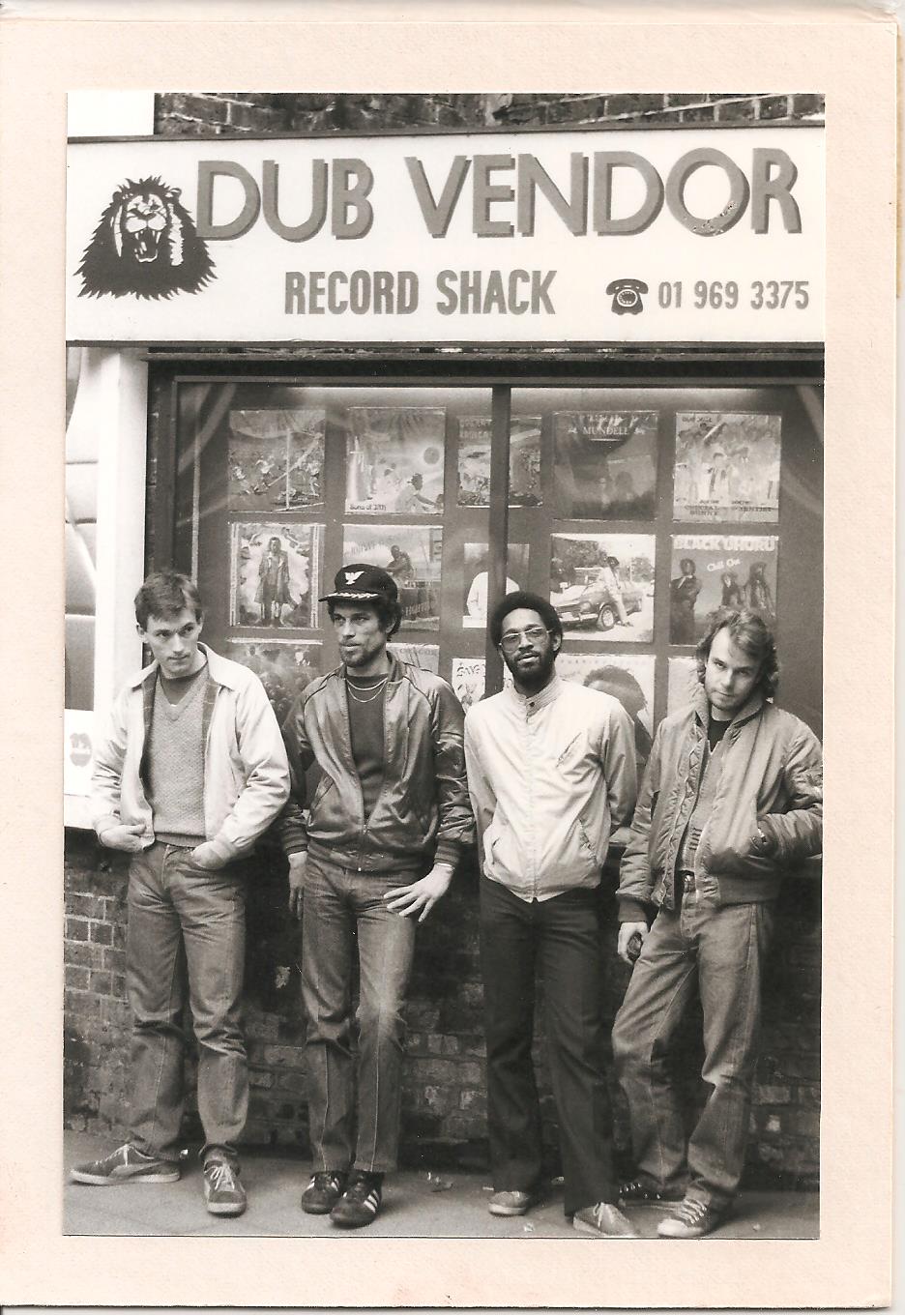

The book goes on to chart the changing face of the country’s record shops during the mod, psychedelic and jazz-funk heydays of the ’60s and ’70s, as well as the rise of reggae and punk shops during the ’70s and ’80s. Then come grassroots affairs catering to significant immigrant communities, as represented by Stern’s West African Record Shop, ABC Music, catering to Asian customers in Southall, Haringey’s Trehantiri, serving Greek, Turkish and Kurdish patrons, and the Albanian Shop in Covent Garden. When hip-hop culture takes London by storm, Groove Records plays a big part in fanning the flames, and Sheffield’s FON later gives rise to Warp Records.

Cartwright emphasises that immigrant outsiders often brought shops and labels to prominence. “Going for a Song details a secret history of British and Northern Irish music making,” he suggests. “For example, so many of the greatest record shops were owned by Jewish families — from Levy’s to NEMS to Stern’s West African Record Shop — but this has never been discussed before. Brian Epstein’s granddad fled the pogroms in Lithuania and arrived in Liverpool aged 19 in 1896 and opened the first NEMS in the early 1900s. The story of NEMS’ rise to becoming the most powerful record shop outside London is a great one, and it was overseen by Brian Epstein. And without Brian and the connections he made in London via NEMS, The Beatles would never have got a record deal.

“Then there’s the Irish community and the West Indians and the Indians and Pakistanis; all these immigrant communities settled in the UK and not only did they set up restaurants, but they all opened record shops! People talk about the UK’s amazingly multicultural food scene; well, how do you think the music grew so strong and fertile? Because the youth here were listening to the music that their new neighbours were playing. And where did the likes of Georgie Fame and George Harrison and Brian Eno and Jerry Dammers go to get the sounds that changed the way they made music? From record shops in immigrant communities.”

Of course, the tale has not only been one of smooth sailing. Going for a Song traces the East End gangsters that pawned thousands of stolen records through corrupt shopkeepers and the exploitative nature of labels spawned by certain niche concerns. Worse still is the unprecedented rise of the chain-store conglomerates that homogenised the musical landscape of the 1990s, and the terrible and seemingly unstoppable demise of the record shop in the new millennium, as file-sharing, illicit downloads and online retail took their toll. And then, the surprising postscript of the present, which has seen the record shop rise like a phoenix from the ashes, galvanised by the unwavering loyalty of vinyl junkies and the realisation that phonograph records have sonic and tactile qualities that can never be replaced by digital audio.

The independent record shop now seems on more solid ground that at any time in the last decade, with shop closures no longer commonplace and survivors firmly embedded in the musical and commercial ecosystems. And despite the errors of misguided major labels and mega-chains, Cartwright knows that British record shops will endure.

“Record shops certainly have benefited from the vinyl revival and a renewed appreciation of going to a specific shop to get your music,” he emphasizes. “But first I’d like to consider this: what killed the big chains like Virgin and Our Price in the first place? It seems that the general public reached peak CD at the start of the new century and grew tired of buying so many turkeys; duds with only one good tune on a 70-minute album all determined that consumers stopped paying for shit sonic sandwiches. At the same time the youth chose to download rather than purchase music. Great shops like Honest Jon’s, Soul Brother and Supertone all survived because they had loyal clientele and kept a strong vinyl presence. And it is to these aforementioned shops that the new shops must aspire if they want to survive.

“I’m a realist and aware that the vast majority of music fans are happy to stream or buy a CD at the supermarket. That won’t change – this is the same demographic who shopped at Our Price or taped off the radio rather than buying records. We will never return to the days of a record shop on every high street. What the new and surviving record shops have is a core audience who love not just music but realise that going to a record shop is a ritual of sorts: even if you’re buying a mainstream album from Spillers in Cardiff rather than Tesco’s, then you are choosing to engage in holy communion. You are paying more and supporting an institution that trades only in music, which is in itself a statement. And the kids who grew up on Napster found they had thousands of tunes on their phones but, finally, so what? One 45 can convey so much more than a thousand MP3s. The difference between going to a record shop and using Amazon or iTunes is the difference between slow food and fast food. You want real flavour? Then use a record shop!”

Going for a Song is published by Flood Gallery Press.