“A strange economy”: Amanda Petrusich goes on the search for the world’s rarest 78’s and the curious characters who collect them

Photograph by Amanda Petrusich

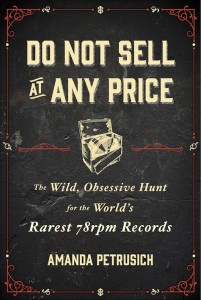

We speak to author Amanda Petrusich about her new book Do Not Sell At Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records.

There’s a little dusty corner of the so-called vinyl revival that has and will forever remain untouched by the hype. It will never be celebrated by an annual international event at the world’s hippest record shops, it is not concerned with the fabrication of limited editions on coloured compounds, and has no time for gatefold sleeves and screen-printed artwork. Confined to the boxes behind the ones you’re looking in, under folding tables at suburban flea markets and at the bottom of that stash of clutter you inherited from granddad’s attic, are the 78s, heavyweight shellac discs that revolve stoically at 78rpm.

Early causalities of the relentless march of audio progress that has since snagged on vinyl records, 78s have been rendered worthless to the majority of record collectors for the simple fact that they are unplayable on standard turntables. Similarly the music they hold – think pre and inter-war blues, ragtime jazz and ballroom easy listening – has been cut adrift from the narrative of contemporary music, a pre-historic era with few obvious reference points. Furthermore, with labels like Revenant, Mississippi and Sublime Frequencies doing a fine job of making this stuff available on vinyl, there’s even less reason to get your hands dirty.

However, like any self-contained system (the art world comes to mind too), 78s have accrued incredible value within their own specialised context. When collector John Tefteller paid $37,100 for a copy of Tommy Johnson’s ‘Alcohol And Jake Blues’ (a record he already had one copy of) its value may have seemed arbitrary, if not somewhat insane from the outside, but from within, the deal was sacrosanct, simply the result of the internal logic of the nichest of markets.

Needless to say, with these sums of money involved, the levels of secrecy that surround the most sought after 78s and the simple beauty of the music they hold, infiltrating that world was always going to prove difficult. Step in Amanda Petrusich, the music writer, journalist and latter day 78s collector, whose new book Do Not Sell At Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records does just that. Diving head first into the scene (and even the odd river when necessary) Petrusich has sought to reveal a fascinating world from within, shedding light on this extraordinary and often outlandish tribe of record collectors who have devoted their lives and much of their disposable incomes in pursuing the world’s rarest 78s.

Let’s start with a bit of context. Could you explain why 78s are so rare/sought after?

Well, 78s are rare in part because they’re so fragile. Most 78s are made from a mix of shellac and various other compounds, and they’re rigid and brittle; compared to shellac, vinyl feels pretty forgiving. If you drop a 78 at the wrong angle on the wrong surface, it’ll shatter on contact, like a champagne flute. Now, 70 or 80 or 90 years after they were made, many of these records have barely survived, and the ones that did make it tend to be pretty battered. Likewise, there are almost no surviving metal masters of these recordings, meaning the records themselves are the only evidence we have that these performances ever happened. So, of course, it all starts to feel very high-stakes: 78 collectors aren’t just rescuing the objects, they’re rescuing the songs.

You encountered some resistance from collectors initially. Was it tough to gain access to the world of 78s collectors?

Most of the folks I ended up spending significant time with were open and generous with their knowledge and their records, but yeah, absolutely, it took a minute! I spent over two years reporting this book, and even after all that time – and I now consider many of these dudes close friends – there were still plenty of things they wouldn’t give up. 78 collectors, in particular, can be protective of their trade. They don’t want the price of records to escalate. They don’t want to reveal their sources to other collectors. Often they don’t want anyone to know what they have or don’t have. As a reporter, that was sometimes a challenge to navigate.

Rather than just document the scene, you seem to have thrown yourself into the lifestyle whole-heartedly. Did that help convince people to open up?

I really think it did. With this book, specifically, I went into it already so invested in this music – emotionally, if not yet financially – and my curiosity about it was so earnest and goofy that I think it allowed me to immediately connect with collectors in that way. Like, ‘Hey, we’re both fans. We are both having an extraordinary reaction to the music contained on these discs.’ Fandom is a really powerful language. I also think my willingness to do whatever it took – an ill-advised reporting technique I probably learned from reading too much George Plimpton – said something about my seriousness. I didn’t just want to write a superficial story about old records and the guys who obsess over them – I wanted to be a part of their world for a little while, to see how it functioned, to see what it meant.

What is it do you think that differentiates a 78 collector from your normal vinyl collector?

Vinyl has obviously had something of a broad cultural renaissance in recent years, and I think it’s considered kinda cool to collect LPs – 78 collecting, alas, is not cool. I say that so lovingly. It requires so much time and thought and money and energy and knowledge; it’s different from going to the Brooklyn Flea and picking up a bunch of old R&B records. And of course, I love old R&B records, and I own plenty of LPs – but a person can dabble in vinyl, whereas serious 78 collecting requires a complete and total submission to the task. There’s an obsessiveness to it. Part of me empathized with that – I was listening to an interview with the writer Nathaniel Rich recently, where he talked about writing itself being an obsessive act, which is also true. I got it right away. There was a part of me that just understood.

You went on some pretty outlandish quests to find certain records while researching the book. There’s a story about diving?

I don’t want to give too much away, but I did follow a very tenuous lead to the bottom – the watery bottom – of the Milwaukee River outside of Grafton, Wisconsin.

Photograph by Nathan Salsburg

One collector you meet, John Heneghan, describes collecting 78s as a disease. Do you agree?

I actually write quite a lot in the book about the neurobiology of collecting, and I brought that question to a neurobiologist named Dr. David Linden, who’s a professor at Johns Hopkins and wrote a wonderful book about the science of want called The Compass of Desire. The diagnostic criteria for these sorts of things tend to be vague by necessity, but there is considerable evidence that collecting can and should be considered a form of addiction, which of course is a disease – it also shares certain attributes with OCD and OCPD, as well as forms of mild autism. For obvious reasons I’m not comfortable diagnosing anyone with anything, but I do think there are some underlying physiological and psychological cues at play with this behavior.

In an extract we published last year from Record Collecting as Cultural Anthropology, the author describes collecting as just focused consumerism. Is there a consumerist aspect to collecting 78’s or is it too out there and specialist for that?

It’s such a strange economy, because 78s are objectively worthless. If the song is no good or the artist has no cache or no one else wants it, then you’ve just got a weird, heavy disc on your hands. Also, a lot of the major deals happen in private, and often they’re trades – it’s fairly unusual for a big, public, cash deal to happen. Although of course, every once in awhile, it does – like when John Tefteller, another of the collectors featured in the book, acquired that Tommy Johnson record for $37k on eBay last year.

At the time when the Tefteller deal went through last year, I remember reading something about the etiquette when making deals of this magnitude with cases of theft, forgery etc. pretty common. Is there a shady side to all this, when the obsessive elements and sums of money involved go too far?

It’s funny, I didn’t see too much of this firsthand, but I did hear stories about it – records getting stolen, records getting snapped in half. Rumors have circulated for years about Bob Hite of Canned Heat – that whenever he would find a copy of a rare 78 that he already owned, he would destroy the record so that his copy would be worth more. There is a lot of paranoia at play in this community, and perhaps with good reason. There are also a lot of soured relationships.

Could you describe one or two of the personalities you encounter while writing the book?

This is such a personality-driven subculture, which is partially why it was so fun to write about. I never go to meet him – he died in 1991 – but I spend a lot of time in the book talking about Harry Smith, who was an extraordinary artist and person (the Anthology of American Folk Music means a lot to me) but who also sounded like a very, um, challenging guy to be friends with! I heard lots of stories about Harry stealing things from other people because he believed so strongly in serialization – that other people’s things belonged in his collection, where they could then be slotted alongside whatever else he thought they belonged next to, following whatever he imagined to be the proper continuum.

Amanda Petrusich

While there’s an obvious personal angle to the book, there’s also a large cultural significance in these collections. Could you explain that a little?

For me, as a fan and as a writer, this was a very personal story, and it’s certainly written that way – it’s a first-person account of my time in this community, and of the music that was or is being excavated and preserved by these men. But the historical significance of the collector’s work is what drew me to this story in the first place – in a way, I feel like collectors continue to be criminally underappreciated for the work that they do. So much of what we now think of as the accepted canon of American music – all the early jazz and blues recordings that, inadvertently or not, influenced everything that came after – was collected, celebrated, contextualized, and saved by 78 collectors.

What your favourite 78 and why?

This changes all the time for me, but my most reliable answer is Geeshie Wiley’s ‘Last Kind Word Blues’, which I’d heard on various reissue compilations but was first played for me on 78 by the collector Chris King. I am so thoroughly destroyed by that song. I can’t even parse my reaction. I just fall apart.

What do you look out for when going shopping for 78s – although your subjects were reticent to share their tips, could you give us one!?

Always look inside the cabinet of a gramophone – people are always shoving 78s in there! Also, in an antique or junk shop, sometimes books of 78s – the original “record albums” – are shelved with books and not with records. It’s always worth scanning a bookshelf for that. 78s tend to be on the floor because they’re so heavy; now, I’ll walk through a flea market or antique store with my eyes focused solely on the ground. But the best advice is just to not give up. Good records are out there.

Do Not Sell At Any Price is out now and available to order via Amanda Petrusich’s website.