Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Massive Attack: Kazim Rashid on music and cultural identity

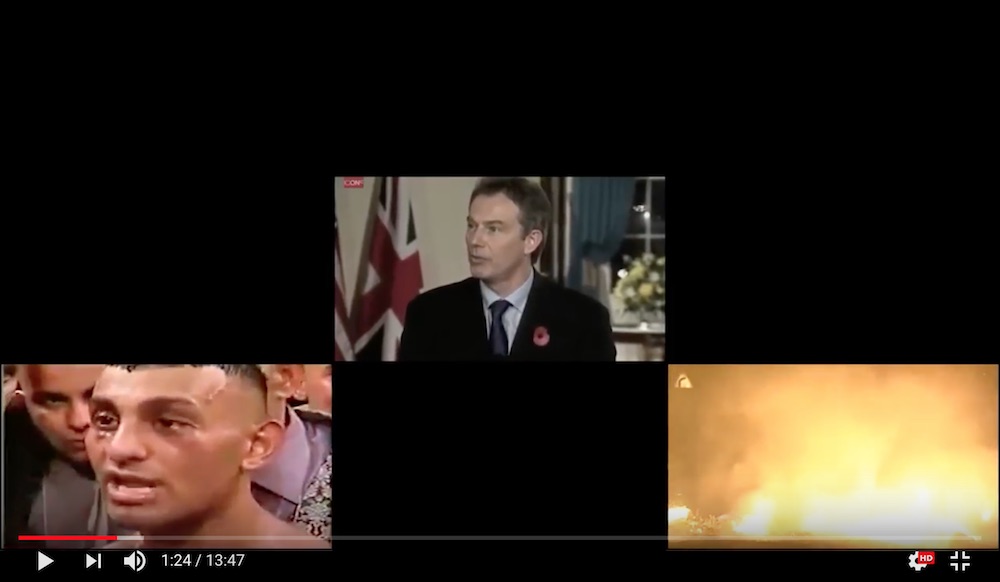

In his new audio-visual work, Kazim Rashid explores the seismic socio-political impact of 2001 on brown identity in the UK and across the world. Juxtaposing images from the aftermath of 9/11, UK boxing legend Prince Naseem, and the Oldham race riots in the video piece set to be presented in London next week, Rashid speaks to Kieran Yates about the hybrid relationship between music and cultural identity.

How do you solve a problem like generational trauma? It’s a question artist and curator Kazim Rashid has been grappling with. His answer, if not to solve, but present, is through art. Or more specifically, curating work that confronts cultural trauma head on. His most recent work, an audio-visual film titled 2001: Pressure Makes Diamonds posits that 2001 was a turning point in modern cultural history which led to what he calls “a post-traumatic fracturing” of identity. Rashid uses 2001 as a case study that, to him, is identified by three key events: three months of race riots in his home town in Oldham in the north-west of England, the events of 9/11, and the crushing defeat of Prince Naseem as he lost his first ever fight.

Rashid is sitting at my kitchen table, sipping tea as he talks me through the film that we stop and play, chat through, rewind, and play again. He’s dressed all in black, and if you were unaware of his work you might call him unassuming.

The work is anything but. In fact, it’s the humour and archness that underpins his work which makes it so fascinating. Confrontational, surprising and always delivered with respect, he has previously worked closely with collaborator Gaika and Dazed, across countless creative campaigns, and two years ago, wrote a piece titled, ‘Where did all the brown people go?’ for himself. With his Northern desi accent twang that is sonic ASMR, he talks about what it means to be brown and explains that language isn’t a barrier to access brown culture. “We know language isn’t the only language – how people communicate isn’t just through words,” he eye rolls.

Rashid grew up in Oldham, on a street where there was only one other brown family “at the bottom of the road”. “There might have been a bit of cash knocking around,” he describes, “but it was always culturally working class”. He grew up “obsessed” with new jack swing and R&B, citing artists like Teddy Riley and Blackstreet. He recalls hungrily buying Shola Ama and Janet Jackson records in school, while spending the rest of the time with his family – subconsciously imbibing the Qawwali music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan in the house, going to mosque every Friday, visiting cousins on the weekend, and being aware of ihs difference in a majority white school, but ticking along in the naivety of childhood. It was 2001 when the Oldham race riots – some of the worst race-related violence that his country has seen in its modern history – would take place on his (literal) doorstep and last for three days.

“It was… so surreal,” he says. “Going to school during the day was scary. My dad got attacked outside the house in our driveway. I felt really, really afraid. I remember thinking, I hope people don’t know what I eat at home.”

He describes an attack he witnessed on his father with a tone that is still incredulous: “Some kids jumped him, and the door of the car came off and it was red – we had to get a new one, a yellow one because we couldn’t afford to replace it. And I remember it being so potent, this yellow door… I want to do a piece around it.”

The physical symbol of the yellow door and its flippant poetry is a brief but thrilling step into the mind of Kazim – it’s these visual signifiers of your social status, your skin, your local geography – that inform his work. And it’s through these signifiers that Rashid celebrates culture and community and mocks the rhetoric of far-right spokespeople.

Rashid reflects on these events in his film via archive footage, television static and a soundtrack that he says “reflects a shared language between immigrants.” Rashid’s audio-visual work is influenced by the sounds of his childhood, including Hindi prayer ‘Hare Ram Hare Krishna’, Bally Sagoo, UKG, and producer MA Nguzunguzu.

In the film, we start with George Bush’s post 9/11 national address, (“I could have used loads of contemporary footage for this film”), where he condemns the Taliban regime, followed by the call to prayer and Prince Naseem in Vegas. The images are chopped and screwed into a singular moment, one that platforms the demise of a figure of Muslim excellence with Naseem’s defeat, alongside the views of the far-right. The project began with Rashid wanting to make a straight homage to Naseem – “all roads lead to and from Naseem”, he laughs.

“I’m not interested in losing at all, I’m interested in Naseem, about what it means to be a man and for someone who grew up with queer sensibilities, how he as a sex symbol helped me work out how I looked for myself. How I felt about him was the way I felt about Michael Jackson – he transcended cultural expression.”

“How he represents himself culturally is mad to me – he goes from this into ‘Gravel Pit’. He was so lauded by American rappers, with Michael Jackson [in 1997 the king of pop posed for a picture with the king of sports] and Diddy. He laughs as he references the call to prayer that Naseem played on entering the ring, which features in the film. “People think I’ve put that on as some kind of political thing,” he sighs, “but it’s not.” We discuss how the the sonic sweetness of the prayer has since shifted – in 2018, the far-right use it as an emblem of danger, extremism, an affront to our value system.

As with most diaspora kids, the background soundtracks of home move into the foreground in later life. Confronting the magic of the music that had become part of his muscle memory came later for Rashid, and he retells a moment of hearing a Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Massive Attack remix in a club. “I couldn’t believe it – I bought the vinyl straight away”, he says.

He talks about other cultural hybrids that shouldn’t work, but do. He laughs as he cites the invention if the chicken tikka masala. “It’s what happens when brown and English cultures collide,” he says. “It’s so delicious, but it’s not like anything I’ve ever eaten at home. This is Indian food made for English people but… it’s so delicious!” It’s a flip of the script – you think he’s going to bemoan colonial recipe snatching, but instead leans in and the point is made – “that third space” – the space that perhaps he is part of – is, well, delicious.

Next for Rashid is doing what he does best – curating networks that help realise his vision alongside a community. An exhibition titled 2001: Pressure Makes Diamonds will take place on 11th September – a date that is no accident – featuring a group show of selected works by emerging new voices from the South Asian, Arabic and Muslim diaspora in England as well as Rashid’s film of the same name. For him, this is part of the answer to his previous question searching for brown artists – create a space to showcase them yourself. Whether it contributes to healing trauma might be a longer road, but for Rashid, this is the first step – one Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan track at a time.

2001: Pressure Makes Diamonds opens at Rich Mix in London on 11th September and runs until 30th September. Click here for more info.