From punk to power pop: The records that have shaped 10 years of Captured Tracks

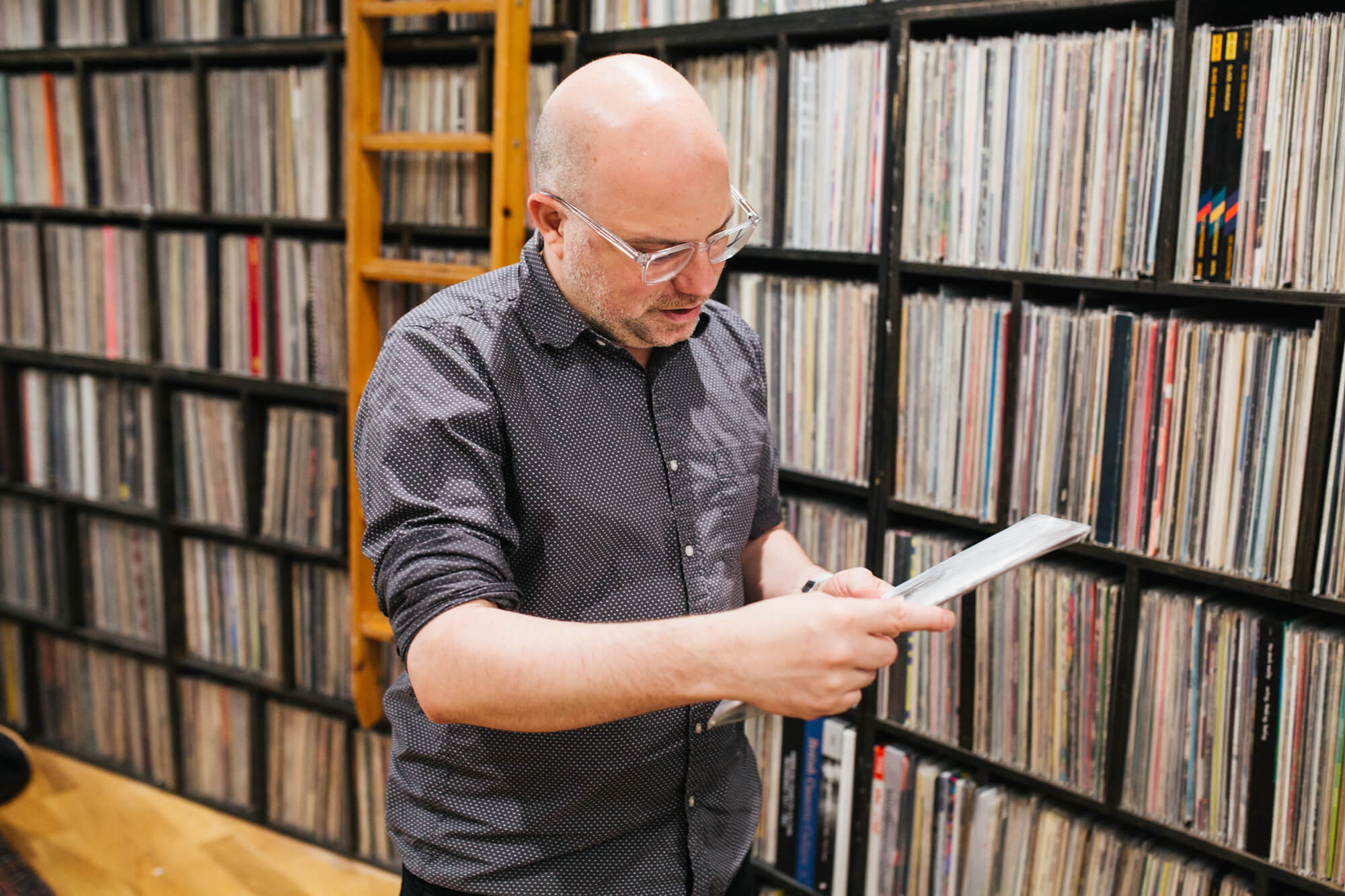

Label boss Mike Sniper digs into his vast collection.

Such is the prolific and diverse nature of Captured Tracks’ catalogue, it’s hard to believe Mike Sniper’s Brooklyn-based indie label has only been around for a decade.

What began as a label of love – born out of Sniper’s frustration with the industry, a wealth of knowledge gleaned working in record shops and a particularly lucrative power pop collection – has since become a widely respected, imaginative outpost for new music and astutely curated reissues.

With striking visuals and the coherent aesthetic nouse to seamlessly release sell-out Mac Demarco records alongside the obscure German synth-pop of Saâda Bonaire, Sniper has honed a label rooted in guitar music that transcends generic boundaries. “People say guitar music is dead,” says Sniper, “but it’s the most idiotic thing to say.”

Picking through his expansive personal collection and the Captured Tracks archive at its Brooklyn office, Sniper shares his story with Barbie Bertisch, through the records that have defined the label’s blossoming first decade.

Let’s start with Blank Dogs. Can you tell me a bit about the band and how that led to Captured Tracks?

I was in a bunch of bands that did nothing in particular and was working at record stores right after college, booking shows and working a bit with distributors. Mostly though I started doing art for labels; bands like Tyvek, Black Lips, and Jay Retard. Blank Dogs started when I was 28 or 29, out of frustration of not finding the music I wanted to play. It was an experiment for me to have fun, but led to friends like Mike [Simonetti, Troubleman Records] and Larry [Hardy, In The Red Recordings] releasing some of my music. It was then that I realised I could do this myself without having to do the touring circuit which was typically demanded of a signed artist. Captured Tracks started right at the tail end of Blank Dogs, when I was no longer satisfied with recording. I know I’m not limitless in my ability as a songwriter, and I accomplished what I wanted. I didn’t want it be a chore, which was great because almost at the exact same time, the label was starting to take off.

Tell me about the Blank Dogs EP which used the Captured Tracks name.

It was called Captured Tracks Volume 1, but I never even thought about recording another one. I was searching for a name for the first two EPs and my friend Cassie from Vivian Girls suggested it. It was better than anything I could come up with on the spur of the moment and I liked that it did not evoke anything. I didn’t want it to sound like something that reminded you of something else. I like labels that have a strong aesthetic and their name supports it, like Sacred Bones – everything make sense. It’s great for them, but for me I wanted it to be more open-ended. Anything could come out on Captured Tracks.

In 2008 you put out about three records, then come 2009 and 2010 you had a zillion. It’s an enormous amount of output for a label that has just kicked off, but it was also perfect for that time.

We call it lighting in a bottle. The zeitgeist.

Exactly. For example, Dum Dum Girls, the first on the CT catalogue. Did you know what you had in your hands?

We were MySpace friends, I had never met her. She had a forthcoming 7″ on Hozac which wouldn’t be out for a while. She sent me four tracks which I loved and that was pretty much it. They weren’t even out digitally, it was just a 4-song EP on a 12”. The first pressing sold out. Ironically, it was sold as a pair with a Blank Dogs EP because no one had heard of Dum Dum Girls yet. So, folks who’d buy the Blank Dogs EP would also get their EP, and hopefully get into them. We know what happened after that. She got interest from SubPop and that’s when the whole rigmarole started. We had a project called Mayfair Set and we even an offer on the table from Matador. But if we had signed to Matador, we would have had to do a lot more work than we were willing to do.

You would have had to tour and do what was expected at the time. It would have thrown the label off its course.

Not only did I really want to do this record label, but I had no interest in touring, and I hated practicing. I liked practicing when I was in punk bands, because it was an excuse to party.

What were some of the early punk records that inspired you?

I had things that I coveted but I didn’t own until I could afford them, like The Victims’ ‘Television Addict’ which I found from a compilation called Murder Punk. It was a $500 record and did not buy it until I was able to trade the original art for a Black Lips flyer for it.

I got into post punk and indie and I stopped listening to punk for a while. Then I got sick of indie rock and got into rare punk. At the same time I started working at a ’60s and ’70s record store called Midnight Records, and they stocked all psychedelic, garage rock music. Punk lead me to indie, which lead me to psychedelic, then back to rare punk and then to power pop, which is how I funded the first two releases — I sold all my power pop records.

Full circle. How do you think all this music informed your role as an A&R at Captured Tracks?

All these records we’re discussing are basically guitar-based records, which is what Captured Tracks is most known for, even though we do have electronic artists. I’ve listened to so much music in my life, ever since I was a kid, that I feel like I can pick out stuff that not only I like, but that, if people are into the aesthetic that we’re trying to put out, they will also like.

Totally! It shows in the releases. Let’s talk about this Pitchfork-era, New York scene in which all of a sudden you’re putting out thirty records a year and you land yourself with Mac DeMarco.

I wasn’t even aware of Pitchfork until I was recording in Blank Dogs. There was this community in NY and SF of punk-informed indie musicians that were making music that people missed. In NY, you had Crystal Stilts, Woods, and Cause Commotion. In SF, you had Thee Oh Sees and Grass Widow pretty much at the same time. They were half-way between garage and indie scenes, and were born out of Todd P’s venues specifically. He gave these bands a place to play, the releases followed, and all of a sudden Terminal Boredom started talking about them. From there, Matador signed Times New Viking, Kurt Vile, Jay Reatard, all these legit indie labels were signing these artists and they got big. We were the second wave. The Captured Tracks bands were Beach Fossils and Wild Nothing…

You also put out early Thee Oh Sees stuff.

John is my friend and he just gave me music to put out. What was cool about that scene, and maybe something didn’t happen in the second wave, was that everyone was very supportive of each other, and it didn’t matter who played first. Everybody went to everyone’s shows. The second wave became less about the scene – the bands really started blowing up, venues closed down, and there was some general malaise within the music industry. Mac [DeMarco] came about because of that. I was opening up a new record store and this guy came back from Montreal and put on what ended up as Rock n Roll Nightclub at the shop. I asked him to send it to me, I reached out to Mac, and two days later we were working together.

All of a sudden, Pitchfork had this interest in everything we were putting out, while we were also very proactively cultivating our own audience. It worked out for Mac DeMarco because of timing, but also because he was this singer-songwriter with more of a John Lennon, Harry Nilsson vibe. From there, it was all sheer personality, force of will, and hard work.

What was a defining record or moment when you realised Captured Tracks was a thing?

That’s easy. May 25th, 2010. It was the day that the first Beach Fossils and Wild Nothing albums came out, on the same day. Beach Fossils was in the New York Times and Wild Nothing got Pitchfork’s Best New Music. I was selling out of tons of records and couldn’t keep them in print. After that, it was off to the races. This was also validation for music my friends were making which I had been around for since day one – telling Dustin to stop putting effects on his vocals, or Jack and I Photoshopping nose hairs from the Gemini cover art. That day set in motion DIIV, Mac DeMarco, The Soft Moon, and Widowspeak. If we weren’t as big as Domino, Matador or SubPop, we had as much space in that sphere from that point on.

Let’s talk reissues. Did you have a specific intention for Captured Tracks?

Well, Radio Heartbeat, my first label was a power pop, punk, and glam reissue label. The Monochrome Set was an early and easy one for me, purely because I wanted the vinyl and it didn’t exist. Something about it fit with Captured Tracks and maybe people who liked them would be into MINKS. I was trying to bridge things. Even Saâda Bonaire fits because we had Soft Metals.

Makes sense. Justin Strauss says hi!

Oh, I love Justin. His first reissue came out on Radio Heartbeat and then we re-reissued it on Captured Tracks as a boxset. This record I heard about when I was 18 at Princeton Record Exchange in New Jersey, and bought for $8.99. The label said ‘Power Pop’ so I took it home and immediately fell in love with it. I’m familiar with Roxy Music and Sparks, but it was almost like there was something wrong with it.

They were like 17 at the time.

I didn’t know anything about them. Then, when I started working at Midnight Records, I’d received so many requests over the phone from Japan for a Milk ‘N’ Cookies CD. I had one of the first vinyl-to-CD ripping devices, and I said one day, “screw it, I’ll rip it and I’ll sell it to this one guy for $100.” A month later, we get offered this Milk ‘N’ Cookies CD made in Japan. So they made like 1,000, and I’m positive this is mine. Fast forward a couple of years and I’m talking to Sal and Justin about putting this out on vinyl, and this CD comes up and I go “that’s my record!” So this record that I bought at Princeton Record Exchange was my CD, then it became the CD, and then it became the reissue that I put out. What a weird story.

There’s also the really funny Capital Punishment story. When I was working at Academy Records, I got a call from this woman whose brother died and he was a hoarder. After Strand took the books away, we arrived and it wasn’t pretty. There were records and porn DVDs everywhere. Tons of bad music, but when you got into the heart of this collection, it became a legendary buy. It took us a long time to get through this stuff and one of the ones I came across was this unknown Capital Punishment record. Then, I see ‘Produced by Stiller’ and B. Stiller. I put it up on my blogspot and years go by. I had this list of records I wanted to reissue, and handed it to this guy called Tim who worked for me. He got in touch with Kriss Roebling, who is also on the record…

Of the great Roeblings of New York!

Exactly. He finds Kriss Roebling, who’s an urban spelunker, because he’s rich. Then, Tim finds out it is in fact Ben Stiller. We waited for his liner notes for three years. He’s a busy dude. The record still isn’t out.

Fast forward to today… how do you feel the sound of the label has evolved?

Current A&R is very traditional. Myself and the staff will sit around a demo and weigh in. The way things have changed is that we’re not fast and loose with our signees anymore. Before, we left it up to a lot of PR, but now we have a lot of overheads and a big office. If we have 40 people around the world working on this record, there’s a certain number of shows that you have to play.

On the other end, sonically, for me, I just don’t think there are as many bands that do what DIIV, Wild Nothing, and the Mac DeMarco clones did. I already have acts like that. Molly Burch, Wax Chattels, and all these bands that we signed sound a bit different. But I also don’t want to throw too many left curves either. I think it would be great to sign a band that sounds like Beach Fossils, but that isn’t them. We now have acts from Australia, U.K., Spain… People say guitar music is dead, but it’s the most idiotic thing to say.

Photos by James Hartley