Published on

October 30, 2015

Category

Features

Musician and composer Oliver Coates introduces the work of conceptual artist Hanne Darboven.

In the Arthur Russell tradition of modern cellists, Oliver Coates straddles the avant garde and the mainstream, as comfortable working with Johnny Greenwood and Mica Levi as he is recording with MF Doom, collaborating with Steve Reich, or performing with the London Sinfonietta.

Drawing a thread between industrial, drone and classical electronics, he has arranged for Boards of Canada and is currently preparing to curate a festival at London’s Southbank entitled Deep Minimalism. Performing at Whitechapel Gallery this weekend as part of their ongoing series of experimental music and art Music For Museums presented in collaboration with The Vinyl Factory, we caught up with Coates to find out a little bit more about his approach to playing the ‘mathematical music’ of Hanne Darboven and how gallery spaces can help dissolve generic boundaries.

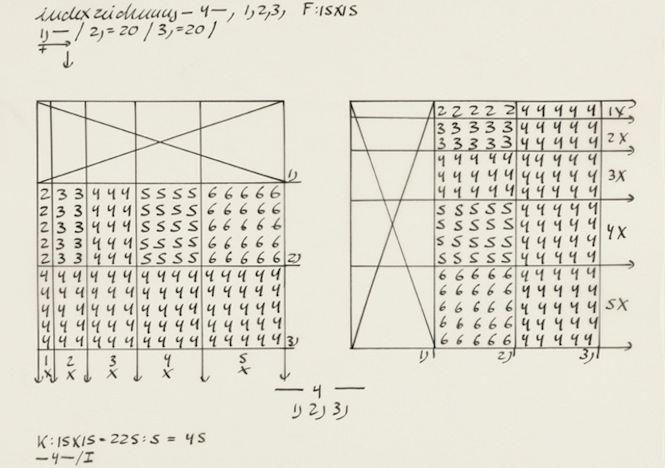

But first, a bit of context. German conceptual artist Hanne Darboven was fascinated with the visual and audible quality of numbers. Working in parallel with pioneering experimental composers like Eliane Radigue, Steve Reich and Laurie Spiegel, Darboven developed her large-scale numeric tabulations into scores for her so-called “mathematical music”, where numbers were assigned sounds that were then adapted into performable compositions.

Hanne Darboven – Photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni

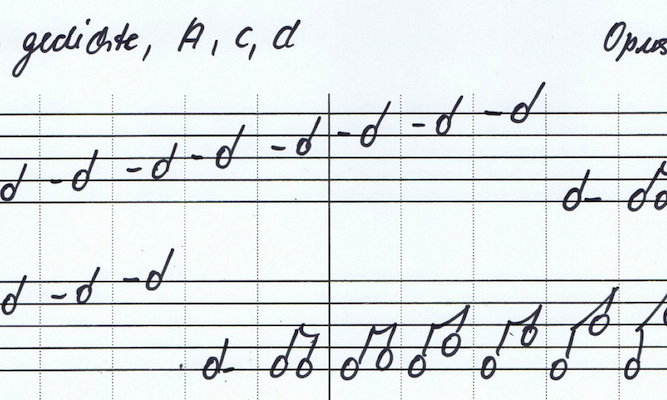

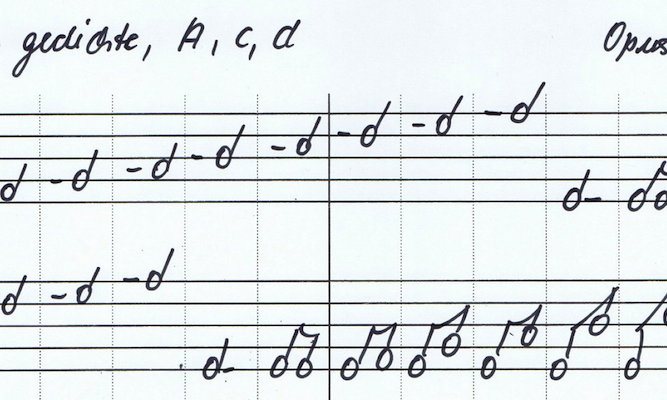

Not displayed until 2002, her 1984 work Wunschkonzert forms the basis of four Opus’s (Opus 17a and b and 18a and b), which, scrawled across over a thousand pages of notations, exploits the repetitive patterns and rhythmic movements of the increasing and decreasing series of numbers. As she obliquely describes: “My systems are numeric concepts that work according to the laws of progression and/or reduction in the manner of a musical theme with variations.”

What is a monumental work of composition, Wunschkonzert takes on an even more extreme quality when performed. What for the listener may be meditative is, for the performer, a feet of stamina and discipline rarely encountered in modern music, as Oliver Coates explains.

You’ll be playing Hanne Darboven’s Opus 17a and Opus 17b, which for those who don’t know consist of 100 continuous minutes of mathematically-scored music. What effect does this have on you as a performer and how do you approach such a marathon exercise?

It’s pretty trancey. When I was asked by The Whitechapel to look into the music of Hanne Darboven I jumped at it. It felt like serendipity. I’ve been thinking about rhythm and repetitive action on the cello for a while, stepping away from long drones and slowly evolving tones to a kind of performance which has a hypnotic flow and constant pulse – a perpetual sense of becoming. The Darboven Opus 17 consists of 100 minutes of tonal arpeggios moving across the most resonant regions of the cello. The physical labour pours into constant patterning. Over time the viewer / listener is more aware of detail in the attack, decay, tempo fluctuations, dynamic and timbre. The warm tones never stop coming. The Whitechapel Gallery has the most beautiful acoustic to play this music in, direct from cello to audience.

How do you retain personality and agency in interpreting the score?

A performer interpreting a score at any level of complexity retains 100% personality and agency. I feel the music doesn’t come into existence without interpretation – in fact the discipline in channeling someone else’s musical ideas is freeing. The performer is placed between the composer and the audience as a conduit for the musical form as it evolves in time.

Hanne Darboven – Opus 17a

While she’s never received the acclaim of male contemporaries, Darboven is part of a rich traditional of predominantly female composers who pushed the boundaries of minimalist composition and computer or mathematically generated music.

This quote from Laurie Spiegel was particularly interesting. “I automate whatever can be automated to be freer to focus on those aspects of music that can’t be automated. The challenge is to figure out which is which.” Is this relevant to Hanne’s work too? It seems to be an area you’re interested in more broadly.

That’s a great quote. I’m thinking a lot about Laurie Spiegel at the moment in parallel with this because I’ve programmed her music as part of a festival at St John’s Smith Square for Southbank Centre in June 2016 called DEEP➰MINIMALISM. Her words apply well to music by Darboven because in one sense she has taken care of texture – it is static, a constant medium of arpeggios with varying notes.

I think of an arpeggiator setting on a synth being left on for 100 minutes. Then the subtle dancing of tones and their partials have an unpredictable life of their own. What the mind chooses to focus on varies – it may even be that the visual rotation in my arm movement will become primary, or an awareness of other peoples’ listening. I phase in and out of different kinds of waking sleep and ecstasy as I play it. I can’t predict that part too well.

Darboven’s scores have come to be termed ‘mathematical music’. What does that mean in this context?

I can’t give great answers to these questions because Darboven was mostly known as a visual artist. I don’t know anyone else who referred to specific music as “mathematical music” – since all music to an extent has a mathematical component. It was a term she used to convey how the numbers and dates in her visual work could be translated into musical notation.

Sol LeWitt wrote this nice summary of Darboven’s work – “The architecture of time. Endless, remorseless, infinite. As fast as the oceans, as short as a wave. It includes all of our lifetimes, and more days, months, centuries. The remote past, the remote future, and now. As simple as a line on paper, as complex as a thousand pages. The scope and elegance of this work and thinking is something that one never forgets.”

Your own work bridges contemporary electronic music scenes and the classical world – these two realms are far from mutually exclusive, but do they find a more natural coexistence in an art gallery as opposed to other venues?

A performance in the gallery helps decondition aspects of musical culture and ritual. The rooms have their history of curated artwork but function as a blank space when it comes to music traditions. There’s no electronic sound in this event but the process behind Darboven’s music (which is derived from a grid of dates) makes me think of sequencers and arpeggiators.

I performed within the Mike Nelson curated installation at the Whitechapel a year ago, playing behemoth cello music surrounded by famous figurative sculptures from history. It’s fun to superimpose a fresh music narrative on older canonic structures, just as Mike fabricated a faked artists studio floor onto which he placed the objects. A happening which is nonlinear breaks up the sense of education or didactic experience.

Oliver Coates play Hanne Darboven at Whitechapel Gallery on Saturday 31st October. Click here to book tickets.

Main image: Excerpt from Hanne Darboven, Wunschkonzert, Opus 17 a and b & Opus 18 a and b, 1984 © Hanne Darboven Stiftung, Hamburg / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2015