Bustleholme: An exclusive video of Napalm Death's collaboration with ceramicist Keith Harrison

Published on

February 11, 2014

Category

Vinyl Factory Films

The day that Napalm Death went to Bexhill to destroy a sculpture with sound waves.

It’s not every day that a grindcore band team up with a ceramicist for a one-off event at the V&A. Keith Harrison’s Bustleholme project was to be his final statement of a residency at the Victoria & Albert Museum which had seen him first draw and then redraw the boundaries of sound and ceramics. Continuing his working relationship with Napalm Death, Harrison’s Bustleholme would pit sound against structure in a ferocious statement on inequality and urban decay. The only thing was, someone had forgotten to tell Health and Safety that it could get a bit loud and the London museum cancelled the show because of fears about the structural integrity of their ancient ceramic vases. But then again, that was exactly the point.

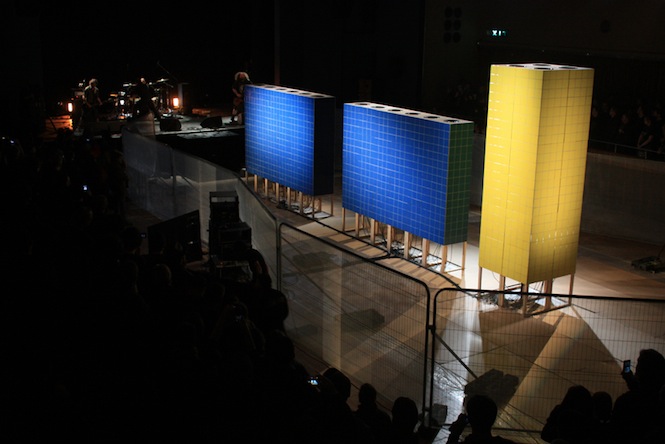

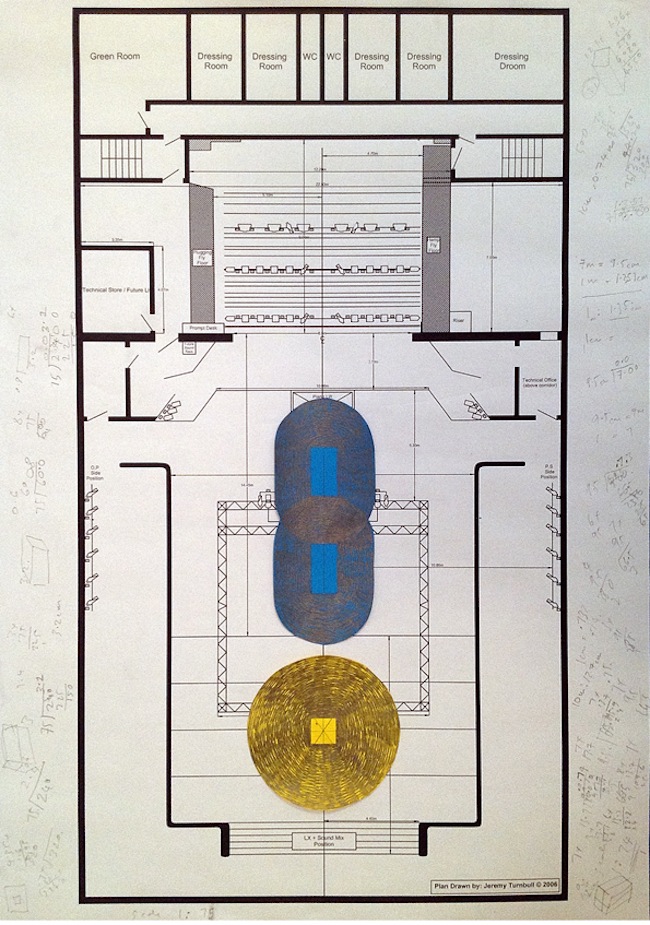

Relocated to the modernist De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill for a show in late 2013, the project centred around three tiled structures (or soundsystems) loosely based on the Bustleholme estate, a decaying utopian housing project in West Bromwich on the outskirts of Birmingham. Positioned in front of the stage, sound channelled from a live Napalm Death performance would be pumped into the hollow structures via high-spec amps and oscillators in order to decay the structures with ear-splitting sound waves in front of a small and unusual audience of metal heads and ‘art wankers’. What could possibly go wrong?

Part installation, part gig, part artistic ‘event’, Bustleholme was never going to pan out as expected. In this short documentary by film-maker Jared Schiller, published exclusively by The Vinyl Factory, Keith Harrison and Napalm Death discuss the concept and execution of their unlikely collaboration on an evening that defied expectations at every turn.

Photo: Katie McCallum

To accompany the video above, we wanted to find out a little bit more from both sides. The following is a combination of our email correspondence with Keith Harrison and our telephone interview with Napalm Death front man Mark “Barney” Greenway, as they discuss the finer points of Bustleholme in greater detail.

Talk us through the initial idea for Bustleholme and your expectations for the evening.

Keith Harrison: The initial idea for ‘Bustleholme’ was that the sound of the band would be contained inside the three soundsystems and the event would be an experiment to see what this contained energy would do to the structure of the work. I was aware from the outset that there was an opportunity to not only collide the band and the artwork but also clash the audience, which would come from two very distinct camps with maybe a small overlap.

Whatever the reason for choosing to come to the show I wanted the audience to be challenged, either by the ferocity and extreme noise levels of the band or by the positioning of the three monolithic sculptures where the crowd would normally be.

It seems like Napalm Death would be perfectly suited to a performance that relied on ferocity and extreme noise levels, but what appealed to you, Barney, about the project?

Barney, Napalm Death: Well generally I’m a big fan of making noise through music, because music, especially these days, has become a little bit trite in some quarters. Certainly music in the mainstream has a certain throwaway appeal to it, but I think music can do a lot more than that.

On the Bustleholme show we used oscillators and they can really make you feel queasy. I like those physiological things you can do where you use both subs and you can mess with people’s guts. I just think things like that have a certain appeal to me. I still get quite a perverse kick out of annoying people with music and let’s be honest, Napalm probably does quite a good job of doing that. I like that all round thing, where it’s not just one sensory experience, it can be several.

As the artist behind the concept Keith, was it just Napalm’s ability to reach certain decibels that attracted you to approach the band?

Keith: I remember them vividly from listening to their rapid fire John Peel sessions, their sound and fury seemed to sum up what it was like living in a post-industrial city like Birmingham under Margaret Thatcher’s socially divisive government.

The involvement with Napalm Death began when thinking about what I would like to do during the residency at the V&A and really wanting to use a live band as the final disruption to finish the series off. Napalm Death’s strong socio-political engagement and uncompromising sound made them my band of choice, setting up the most unlikely collision of venue and band.

And yet, the original V&A show was cancelled, somewhat ironically, due to fears about damage that might be caused by the noise…

Barney: I think the specific considerations were things like vases apparently – some really quite expensive old vases that were hanging from the ceiling. I think they were worried that the kind of noise and vibration we were going to make would dislodge something and either land on somebody’s head or make a very valuable artefact worthless. I can sort of understand it in a way, but also I think how can you not realize that a band like Napalm Death would not make that much noise.

Keith: The project could well have remained a regretful near miss but a number of music venues were interested in taking the event on and when Ollie Catchpole at the De La Warr Pavilion got in touch I felt that this would be the perfect venue due the iconic status of its modernist building and the Pavilion’s function as a music and contemporary visual arts venue.

The project focuses around another “iconic” building – the Bustleholme estate in West Bromwich, outside Birmingham. What was your experience of the estate and did that have particular resonance?

Barney: Me and Keith actually come from the same area, the same small part of Birmingham and the Bustleholme estate was a particularly deprived area, so there was that connection there. I thought the whole sort of thing of underlining it – you know, social decay and literal decay – with him building those structures with the speakers inside, that was the general thing really.

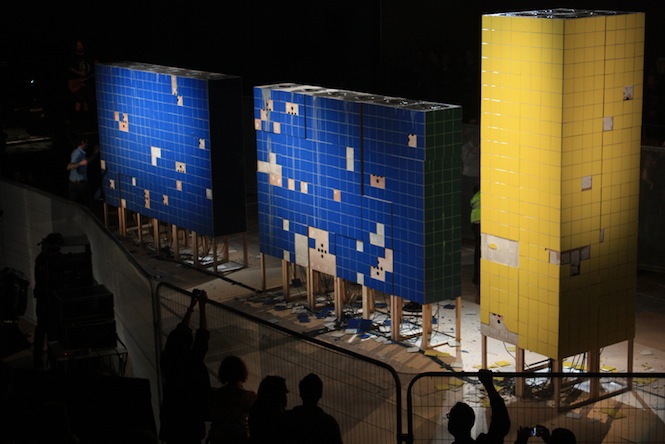

Keith: The Bustleholme estate in West Bromwich was where I was born and lived until I was 8. Located in the Black Country, the heavy industrial centre of the Midlands, three tower blocks depicted overlooked the estate and their vivid blue and yellow ceramic tiles are one of my earliest memories. Despite the subsequent poor reputation of the blocks, at that time in the late sixties and early seventies they symbolised the optimism of a radical approach to social housing rising out of an urban landscape of motorways, canals, polluted rivers and railway lines.

Does the project have an added relevance to the dialogue of social decay, housing and poverty in the current political climate?

Barney: Sure sure, of course it does. But having said that, Napalm have always been kind of, for want of a better phrase, a global phenomenon. It transcends the boundaries of Birmingham, or this country, because my outlook on things is, I’m interested in humanity. I think we all desire a more humane existence, for everybody, not just for us in the West who have comparatively more resources. Sure, Britain has those aspects and the Tories are still playing their old tricks which we’re more than aware of, but it goes far beyond that.

Photo: Asa Desouza–Jones

The evening seems to me like a chain of energy transferred – explosive sound on the stage with the band as power source, the slow decay of the tiled structures and then the reaction in the audience and subsequent destruction of the piece. How did you experience the evening Keith?

Keith: The analogy of channelling and passing on energy is an apt one. The audience were an essential link in exposing the work to let the sound out and in so doing releasing the tension in the auditorium. It was a very different experience for me as normally I am a part of the work as a participant or operator, this time I was in the audience as a fellow observer and it was over to the the band to play, the sound men to channel it and the work to react.

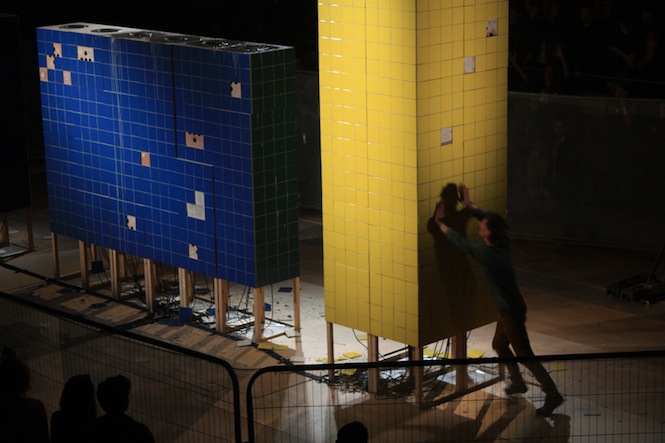

I was close to where the audience member entered the enclosed area and started to attack the structures. I was initially worried for his safety as the tallest block was 4.2 m and unsecured. After he was ejected I felt that it had provided the explosion that everybody was expecting but no one had envisaged happening in this way. It seemed to reflect the history of the estate from idealism to material breakdown to public intervention but it also felt strangely uplifting, as the audience took charge it felt like an empowerment of sorts, a simultaneously creative and destructive act.

Photo: Asa Desouza–Jones

And how about the view from the stage?

Barney: We purposefully picked a very seamless set, basically, we played about 50 something songs, it was all staccato there were no gaps, no let up. We wanted to drive it like a hammer, hammering a nail as much as we could do. Like you say, we’re the power source and we could definitely feel it, also by the response on people’s faces. We got half way through and people couldn’t quite comprehend that we weren’t going to stop, that it was just going to go on and on and on. And then in conjunction with that you can feel the oscillators. It was like a bolt of energy but one that is elongated almost into quite a long block.

Also, the point was it got a bit unpredictable. I mean the exhibit didn’t explode in a great big shower of anything, it wasn’t that spectacular, it was kind of gradual degradation and then some people who attended the gig kind of got impatient and kicked the fences down, so there was a bit of panic with the security people in the venue. But for me that was kind of the point, it was meant to be unpredictable and if people were going to do these things I kind of welcomed it.

Was there a sense of you against the structure? That you had to push yourselves a little bit harder to try and create a reaction?

Barney: Yeah, there was actually, because we were watching it as we were going along and I guess we were willing it to do something. But I think at the same time, for it to explode in a very dramatic way, I don’t think that would have been the point. If you take the element of meaning – the whole point about inequality and lack of equity and human decay – then that surely is a gradual thing and for that part of it, it was good that it came down in pieces, in stages and that people were able to contribute to that as well.

Keith: I hadn’t considered crowd intervention as a possible outcome of the event but the rising levels of frustration in the auditorium meant that it felt increasingly likely that something would give, whether it was the audience or the work.

Photo: Katie McCallum

In a way then it subverted people’s expectations and may not have left them totally satisfied, but in doing so forced them to really think about what the project was all about.

Barney: Well you say that, but ordinarily, as a live band, we wouldn’t use stuff like pyro or anything like that, because we’re not that kind of showy, theatrical band. If we’re going to make an effect like that, we’d rather do it through the music, so the whole point ordinarily for me is through playing fast, playing as noisy as possible with a bass sound that sounds like a concrete mixer. So with Bustleholme, the way it panned out was most appropriate for the band you could say.

In the video, you describe yourself as a “bit of an art wanker” – What art are you into?

Barney: I think, in the music world, one of the guys I find really fascinating is Genesis P-Orridge and for a lot of years now he’s been challenging taboos. I think that people have come to more of a realization in 2014 that taboos are there to be smashed. But people like Genesis P-Orrigde, with his body modification and a whole bunch of things down the years – him really going against religion and stuff – all that stuff was very ahead of its time. On a musical side of things he definitely would be a reference point for me.

Photo: Katie McCallum

What will the project leave people with?

Barney: It would have just been an attack on the senses and there’s that sort of contrast between us being the power source that are pushing it full on to the limit, almost challenging the structure to degrade and the structure itself being a bit stubborn. It’s that contrast really between us hammering at a million miles an hour and the structure deciding when it wants to go down. There’s always that push and pull, it’s almost like a tug of war.

Keith: When I look at the footage of the event I still can’t quite believe we made it happen.

Find out more about Keith Harrison’s work on the V&A website.