Published on

November 9, 2016

Category

Features

Meet James ‘Jimmy’ Rugami, who’s been selling records at Stall 570 in Nairobi’s Kenyatta Market since 1989.

There is a hive of activity in the narrow, meandering alleyways of Kenyatta Market. Women sit on plastic chairs, feet immersed in a basin of soapy warm water in preparation of their pedicures, two ladies at their head, frantically pinning and twisting fake plastic hair into neat braids. In the small, cluttered stalls, there are men bent over sewing machines, making dresses out of the colourful kitenge, whilst vendors walk by selling boiled eggs, Maasai jewellery and pale yellow corn.

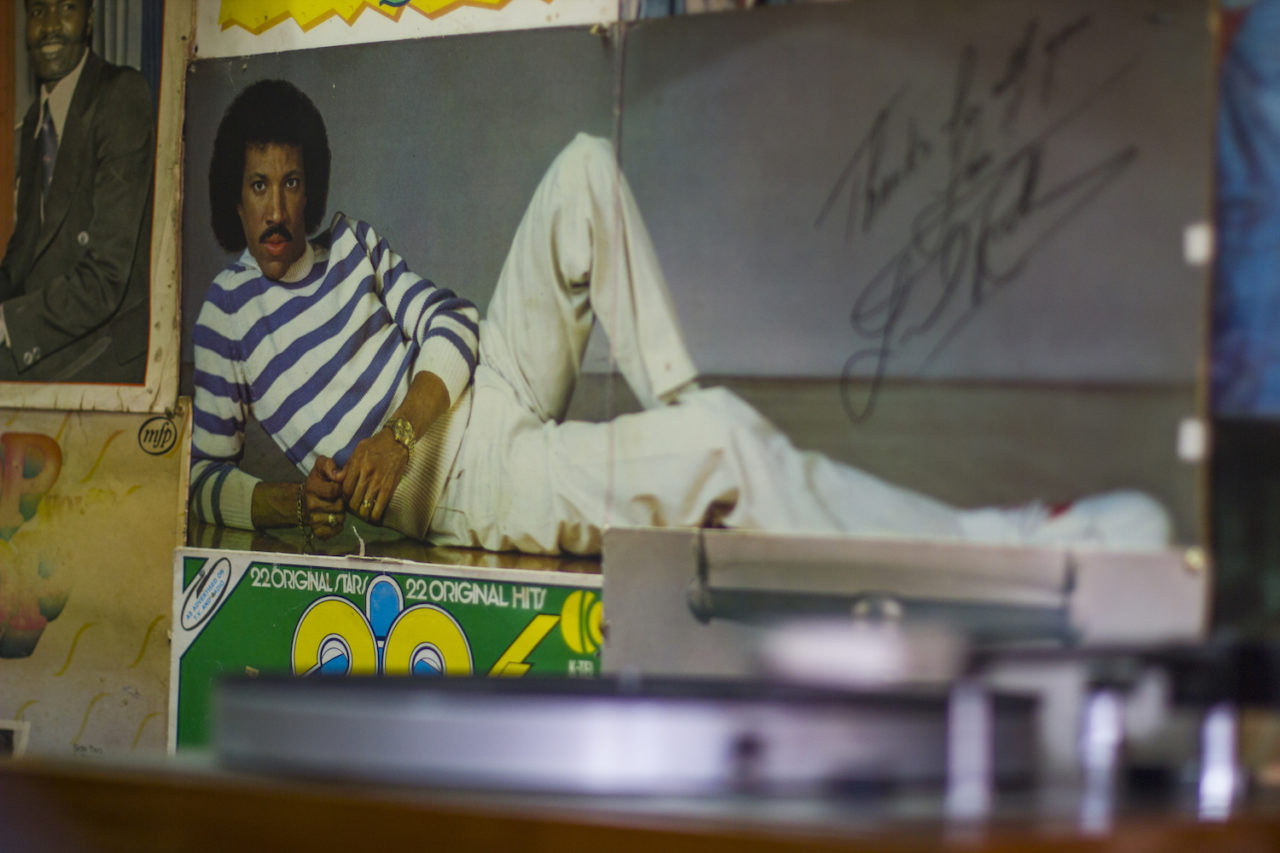

Tucked away in the meat corner of the market is stall 570, where James ‘Jimmy’ Rugami has been selling music since 1989. Raising from an old record player, the sounds of rhumba and lingala waft through the air and mingle with the smoky aromas of roast meat. An autographed poster of Lionel Ritchie and Mariah Carey’s sultry expression stare out from one of the walls, invisible due to the posters and LP sleeves – anything from the Clockwork Orange soundtrack to Tabu Ley’s Afro-Cuban classics and Motown Disco – plastered over them.

Right here, between the stalls selling beef and goat meat, is one of a handful of places in Nairobi trading in vinyl records. Although the city was once the musical hub of East Africa, with scores independent record labels and multinational record companies establishing their regional headquarters here and a pressing plant which was in operation until the early 1990s, vintage records are hard to come by. In downtown Nairobi, off a noisy street by the bus station, is Melodica Music Stores, one of the few places other than Jimmy’s place that sells records. Established in 1971, Melodica recorded and produced hundreds of East African records, many of which can still be found, piled high and unplayed, in the shop’s storage room. But while Melodica is a treasure trove for original, untouched African singles, Stall 570 is the only place in the city which has a large collection of used LPs and singles for sale.

Divided between two adjacent stalls, the shop is crammed with records, tapes, old record players, a few vintage film cameras and even some old shellac discs. Jimmy, a friendly man in his sixties who is never seen without his flatcap, can usually be found unpacking boxes of newly discovered vinyl treasure troves or digging out records for his customers.

“My family was not a musical family. The first time I saw a radio – not a record or cassette player, just a simple radio – was in high school. There wasn’t a record player in our home until 1979” says Jimmy.

In the 1980s he was making a living trading in clothing in Meru, a town at the green and fertile foothills of Mt Kenya, when an itch for something more exciting and a broken record player gifted to him by his brother kickstarted his new business venture. “As soon as I fixed the machine I drove to Nairobi and spent all my savings on records. That was 1986”.

“The music scene used to be quite vibrant, I was always invited to DJ at disco nights at the local clubs and especially at the army barracks. I used to spin mostly African stuff – local records in Kikuyu and Kamba language and few in Zairua, the music of current day Democratic Republic of Congo,” says Jimmy.

But the erratic DJ lifestyle started taking its toll – “I loved life in the fast lane, with all the partying and the ladies,” he says as a poorly suppressed smile creeps up his face – and Jimmy moved with his family to Nairobi in search of something more stable. Thus, in 1989, the now legendary Kenyatta Market stall started selling music, crammed between butcheries selling beef, goat and chicken meat. Little has changed since then: the shop has expanded to incorporate the stall next door, the variety of genres has grown and the customer base widened, but the charm of the place has remained intact.

“The location is pretty cool, I’m glad he chose to stay at the very local ambiance of Kenyatta Market” says Thomas Gesthuzien, a collector who has spent many blissful hours digging in the store.

The shop has survived the decline of vinyl, the popularity of tapes, the birth of CDs and the threat of piracy by adapting to the changing trends. In its early years it sold mainly tapes, which Jimmy would source from all over East Africa: “I used to drive all the way to Dar es Salaam, then take a boat to Zanzibar and buy tapes there. That’s where people were supplying the best stuff, especially jazz, which in Nairobi was either unavailable or very expensive.” But while records were not selling at all, something told Jimmy to buy vinyl whenever he came across it, and he soon accumulated a large collection of foreign and African records. He could go for six months without selling one, but Jimmy could just not stop collecting them.

“I began noticing a difference about 10 or 12 years ago, people were coming into the shop and paying more attention to the few records I had here. I started bringing more in and slowly but surely they started selling.” Now, the shop sells almost exclusively vinyl, mostly old Western music, with a large collection of East African 7″s and some 12”s. One side is where the albums are kept, while the other houses a large collection of singles. Tucked away on the bottom shelves in one of the corners are the Kenyan ones, divided into the various local languages: Swahili, Kikuyu, Kamba, Luo, and Luhya. Next to them is an equally large selection of Lingala – the language of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“He’s the only one catering for a growing Nairobi crowd – especially born Kenyans, not just expats – of vinyl lovers, and he does so with true passion for the music,” says Thomas, who came across a mention of Jimmy’s place online five years ago. Thomas – aka Gioumanne/J4/Jumanne – is a DJ and collector who does research and licensing for reissue labels Strut, Soundway, Afro7 and Rush Hour. He’s been running African Hip Hop – a website whose goal is to ‘unify everybody who’s inspired by hip hop and by the cultures of Africa and of African origins’ – since 1997 and has recently been working on the Kenya Special Second compilation by Soundway records.

“I found one of the first records for the compilation at Jimmy’s. It’ an afro rock single by a band called Awengele, and when I put it on the turntable, he jokingly said: ‘If I’d have known about this, I would have kept it myself’ and proceeded to sell it to me at a very favourable price,” Thomas tells me.

Jimmy says that while most foreigners come digging for African stuff, Kenyans have an eclectic taste, with local and international music being equally sought after.

“At home we listen to everything from African to international rock, blues, soul, pop, instrumental, classical and reggae,” says Angela, one of Jimmy’s regular customers. “I grew up around music and the old Philips record player has always been at the centre of our family gatherings.” Until she heard about Jimmy’s place, Angela would buy records online, “but”, she says, “the real joy of going to the Kenyatta market stall is spending hours digging around and looking for that one treasure.”

Local interest in East African music is definitely on the up, as demonstrated by the popularity of initiatives such as Santuri Safari – Santuri meaning ‘vinyl’ in Swahili – a loose network of DJs, producers, musicians and cultural activists who aim to ‘bridge the gap between traditional artists, instruments, rhythms and cultures and the cutting edge of the global underground music scene’. Esa Wiliams – the UK based South African DJ whose name can be found on the acclaimed Highlife World Series– is part of the Santuri network and visited the stall in 2015 with Santuri co-founder and British DJ David Tinning. “I was more interested in the story behind Jimmy, the records he’s been collecting and also how he initially ended up in a meat market,” says Esa. “We spoke for a couple of hours on the history of the shop, his regular customers and the collection, and after that I had time to dig and get a few from his collection – Letta Mbulu, Tabu Ley Rochereau.”

David Tinning, a veritable vinyl aficionado with a passion that encompasses anything from Jamaican dub to afro funk, disco and techno, came across some ’80s boogie and disco records to add to his collection. “Lots of them had names of their previous owners – often bands or DJs that were active in Nairobi in the ’80s or ’90s – which I find fascinating.” Kenyan Santuri co-founder Gregg Tendwa has come across a few Benga tunes for his archives, a useful find as he also the mind behind Bengatronics – a sound which blends ‘cutting edge electronics, irresistible Benga rhythms and sweet-as-sugarcane guitar riffs’.

Thomas agrees that young Nairobians are listening to East African music with renewed interest: “when I showed up at a monthly event called We Love Vinyl playing 100% local music – often sourced from Jimmy – people looked at me weirdly, but ultimately they loved it and the mere availability of these classics and forgotten recordings have helped turn young people onto their musical heritage.”

But as the popularity of African music increase among both Kenyans and foreigners, acquiring stock is becoming increasingly difficult for Jimmy. “Sadly, as you can see, this is the only African 12” we have,” he says, pointing at a shelf and a small pile of boxes. “There is no more production around here and they are becoming harder and harder to get.” Sometimes people bring in their LPs and ask Jimmy to digitize them; “but other times”, he says “I am forced to act like a predator”.

He has a network of point men in different regions of Kenya, and some in Kampala, Uganda, who inform him when they come across people with a large stock. “If they do not want to dispose of them, I give their families my number, and I wait.” On one of my visits to the stall, Jimmy has just received a large hoard of LPs, mostly African and in great condition. “These were just given to me by the son of a lady who passed away two weeks ago. He is not interested in keeping them, so I’ll give him some money and the music on digital format in exchange.”

Despite the challenges in sourcing good quality vinyl, Jimmy is positive that the future of stall 570 is bright.

Esa too agrees that the little stall in the meat market is made of hardier stuff than most record shops: “places like Jimmy’s will always be around as trends come and go; they may not be as popular as the records stores in the West but they keep the vinyl spirit alive.”

For Jimmy, the store is about identity and roots as much as it is about music. He believes that it would be a great loss for future generations to forget their musical history, and is always keen to pass on his knowledge to younger customers. From time to time he welcomes school parties and teaches them about East Africa’s musical traditions.

“A new breed of talent is emerging in these communities”, says Esa, “and it’s important to have a place like Jimmy’s as a reference to access all the different styles of music that were released across different regions in Africa.”

Having been the only one in charge of the stall since it started, Jimmy’s only worry is who will take it on. He already works seven days a week, and seldom takes a break, afraid of missing out on the opportunity to help someone find their new favourite record. “The challenge is to find someone who wants to do this out of passion, not for money” says Jimmy; “for me, this has been a labour of love. I’ve put my children through school and university thanks to my record shop, but no one is ever going to get rich with it”. Thankfully, Jimmy’s nephew Patrick shares his uncles’ interest, and, in Jimmy’s’ words, is being ‘groomed’ to take on the shop. “I do have plans to expand” says Patrick, “but I would never move it. This place has roots. Stall 570 is where this place was born, and where it will always be”.

Photos: Rachel Clara Reed