Published on

August 13, 2013

Category

Features

Co-founder of the prolific reissue label Mississippi Records Eric Isaacson breaks radio silence to talk about the American folk tradition, field recordings and existing offline.

I arrange to meet Eric Isaacson hours before his third show at London’s Café Oto. The event, essentially a lecture connecting American archivist Alan Lomax’s extensive collection of field recordings and videos with Isaacson’s small but hyperactive Portland label Mississippi Records, is sold out for the third night running. Isaacson is faintly astonished, if not a little embarrassed.

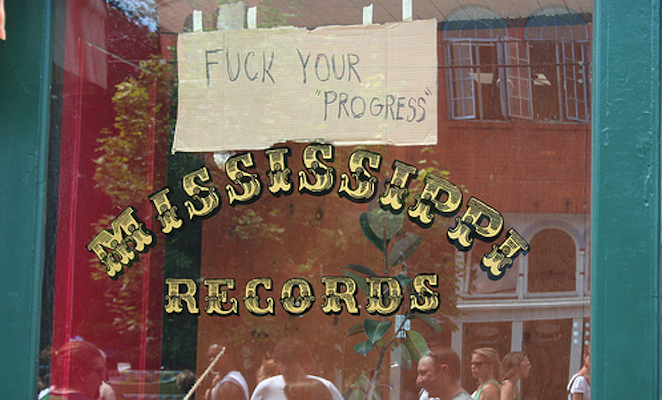

The label, like shop from which it takes its name, is hard to pin down. With no internet presence beyond an entry on Google maps and a half hearted attempt at an illustrated discography by a bloke called Bryan Sinclair which was abandoned in 2009, Mississippi Records is a 21st century anomaly; an online black hole, with over 150 releases to its name.

Knowing this I was encouraged when I succeeded in making contact with Eric via email. We arranged to meet in a café in Shoreditch, and although Eric doesn’t own a mobile phone, he made sure I’d find him, describing himself as “wearing all black, somewhat balding, and have a beard to boot”.

Although his description lends itself to the image of a man who’s spent seventy hours a week over the last ten years in the basement of his record shop trawling through archive material and field recordings from African water drummers to America’s unsung folk troubadours, Eric Isaacson is far from your average retiring librarian.

A charismatic speaker with a rapid tongue and an ear for self-deprecation, Isaacson first founded Mississippi as a record shop in Portland with friend Warren Hill; a haven for the city’s offline eccentrics, who used the shop as a base to register their own releases; the curiously titled Duck Duck Gray Duck, an audio documentary about police brutality and a memorial record for a local guy who’d passed away among several others.

Although just a passenger during Mississippi’s incidental early days, Isaacson has always been a keen collector. Before he was ten he’d already assembled whole Beatles albums taped from the radio with complete track-listings, compiled tapes of RnB oldies with the sax solos edited out (a testament to his strident taste) and found inspiration in the form of Sun Ra’s El Saturn Records, Smithsonian’s Folkways, Harry Partch’s Gate5, and more recently the likes of Honest Jon’s and Sublime Frequencies. It was only a matter of time before the man with the words “Patience is a minor form of despair disguised as a virtue” printed above his desk took the plunge.

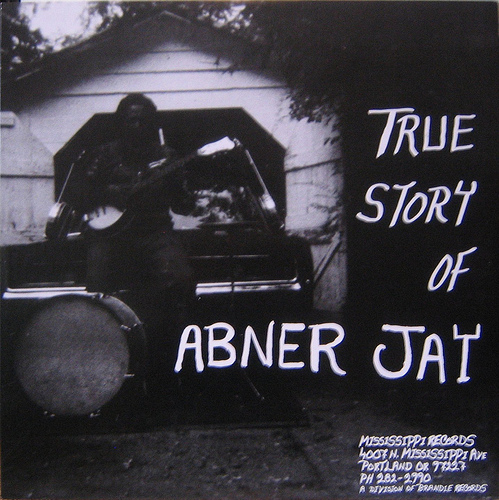

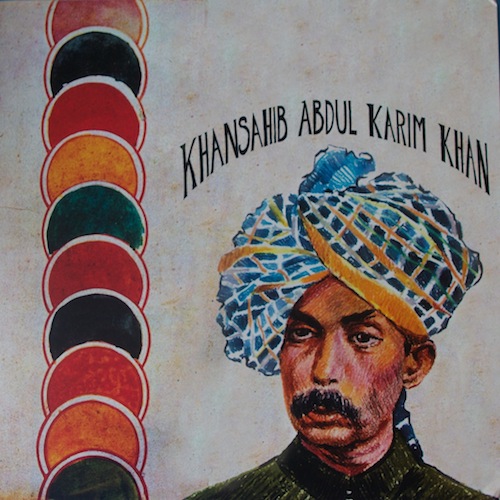

162 records later, and not a drop of ink spilt on publicity, press or promotion, Eric Isaacson has emerged from the basement of Mississippi Records to talk about the label for the first time. With LP’s covering the world folk tradition in the broadest sense, from the outsider blues of 30-year old centurion troubadour Abner Jay, to Theremin virtuoso Clara Rockmore to palm wine melodies of S.E Rogie, his is the label time forgot; a discography of hand-made covers from personally curated releases that straddles the competing ideologies of America’s two greatest folk archivists, Alan Lomax and Harry Smith.

In the early days of Mississippi, its sounds as if the label was inadvertently documenting the local Portland community. Once you started releasing music more actively, how did you go about choosing the records that began to define the label?

Well, I’ve been collecting records for a number of years so at first it was stuff from mine or Warren’s collections, just stuff we’d been stock-piling over the years. When I started I made a list actually – I’m really big on lists – I made a list of 300 different projects I wanted to do, which has now grown to about 1,800 projects. I just had this growing list of dream projects, 300 records that I thought needed reissuing and I sort of started crossing them off and just started playing detective on this list of 300 and that’s sort of what generated the original ideas.

Considering that the label doesn’t have a website, but has managed to grow to 150 releases…

…162 releases actually…

…162 releases, how has news of the label spread?

It’s been good old fashioned word of mouth more or less. To be fair the real way we scored was that early on we got very good distribution. We never sought it out, it just came to us. Like my first records, I put out 500 of each and somehow Honest Jon’s, for instance, in London, got wind that we were doing this and called us and said “Oh we’ll take 300 of each of those and sell them in London”, so I got other people to do the dirty work of distribution and publicising and all that for me.

I got very spoiled and in terms of the internet. It wasn’t a political decision, it was more of an aesthetic decision, or even more a lifestyle decision where I just didn’t find the internet all that interesting and it was kind of boring for me to look at and deal with so I just never bothered to deal with it. What else do I have to gain from the internet? Notoriety? I don’t care about that.

So we became a very sneaky label in that we managed to find a way to get our records into every record shop in the country without having to do anything. We’ve never done any promotion, we’ve never called a record store or distributor, not once. It’s just been word of mouth and it’s just been very organic and we’re incredibly lucky that way.

It sounds like the label sort of mirrors the artists that you put out, who never sought fame, but perhaps made a record which disappeared, only for you to come and seek them out.

Yeah we definitely mirror that and it’s fitting for the music that we do. Also a lot of why I stay off the internet and why we’ve done it the way we have mostly by word of mouth is that I believe that how you appreciate something is based largely, say 90%, in the context in which you experience it in and 10% on the actual content. So if you first hear music on a record, or you first hear about it because you go to a friend’s house, or you just see the cover in a record store and it speaks to you, that’s a great way to discover a song or an artist or to get into a journey. It’s a really beautiful and a little more poetic and a little more nuanced way than the other alternative which is that you see an ad in a magazine for it or you see it on the internet somewhere or read some article in some magazine about it.

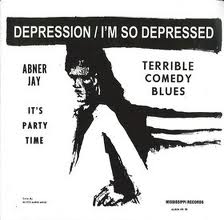

Aside from an unlikely article in Vice five years ago, your records don’t necessarily lend themselves to media attention anyway. Tell me a bit more about Abner Jay, who seems to hold a particularly special place in the Mississippi discography…

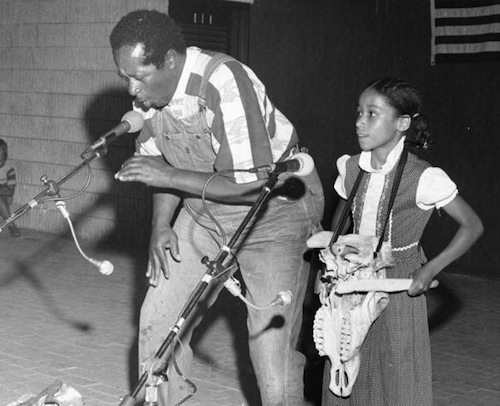

I think he’s a very major American folk song stylist. He was like a one-man-band and he would travel around in a trailer that he’d built that also folded out into a stage and was a travelling troubadour for a lot of his life. He made his own records in editions of 3-500 but they’re mostly dirty joke records, elephant diarrhea jokes, shit like that. But then suddenly in the middle of all these penis jokes and vagina jokes he’d play the most beautiful song you’ve ever heard in your life and then he’d go back and do his comedy routine, so that kind of obscured how good his music was. When I presented him I got rid of the jokes, but there’s a lot of interesting stories I could tell about him.

Go on…

His whole thing was the way that he presented himself and he changed his image a lot. In the 60‘s we would call himself the “Black Bob Dylan” and he would do more conventional folk material, you know, singer-songwriter, sometimes politicized folk material, but then he changed his image later on and he actually started dying his hair grey and would say that he was over a hundred years old even though he was just in his late 30’s.

He would present himself as the only musician still playing Black American music the way that it was played from the beginning of the country to the late 1800’s. He had this whole image of himself as this ancient troubadour who was playing this forgotten kind of music even though in reality most of the songs and styles were very unique to just him. I love artists like that who create their own mythologies and their own universes that are self-contained, but contain more truth in a lot of ways than somebody who would just be honest and boring.

In your presentation you also mention Sun Ra’s Alter Destiny in this context. Creating mythologies at odds with mainstream American thinking is also something that is, commercially speaking, completely unsalable…

Yeah, it’s a very unsalable image. He actually claimed that he was born on a slave plantation that time had forgotten. So emancipation happened in the mid-1800’s in America, but on this slave plantation the white masters just pretended like emancipation never happened and it was operating still into the 1900’s. Abner claims that he was raised in this environment where he was a slave essentially and then he escaped when he was a teenager, so that’s where his mythology came from.

Since the personalities behind the music are so important, is there not a danger of re-mythologizing them?

Well we do re-mythologize people, I mean when you look at anything you change it, that’s science, and so I’ve gone deep into believing that anything on my label is going to be tainted by the fact that it’s on my label. It’s going to be experienced through that lens of something that’s on the label, so I’ve accepted that and hopefully I’m not the only interpretation of these things in the world. My goal is to make a record, that’s precisely what it is, it’s a record – one way of preserving their thing that’s out in the world.

Is it fair to say that Mississippi Records aims to give a platform and a voice to musicians who have been disenfranchised in some way?

It’s a purely aesthetic thing, we’re never looking for the political back-story. It’s always emotional tone first and if it relates to my emotions then it comes out and if it doesn’t then it doesn’t, so it can be everything from Eastern European immigrant music to the recent immigrants to America like the Nightingales and Canaries record to Abner Jay, to some punk records to a million different things really. There’s no real limitations. Well, actually we have one limitation which is that I hate well-produced music, I despise it. Well I shouldn’t say well-produced I should say professionally produced music. Stuff that’s made in a studio and sort of very clean and processed sounding. So almost everything on our label is made in either a small or homemade studio or is a home-recording or a field recording. I tend towards those.

Do you go and do your own field recordings or is it all drawn from source material and archive material?

It’s all drawn from source material. I work with some contemporary field recordists and I go through their stuff with them and make some records but generally speaking I work mostly with archival material. I just don’t have time to travel or live in the real world that much, so I tend to hide at home and receive things in the mail and work with them as I can.

If somebody gave me a million dollars I could spend it all on pressing records tomorrow. The only thing that determines our schedule is how much money comes in every week and we just gather gather gather and once we have enough money we just press another record. Right now there are 28 records on the shelf and I’m just waiting for money to continue that path.

That’s interesting because from the outside, I think I came with the expectation that Mississippi was an archival label of sorts, documenting things for their historical and contextual interest, but actually that’s not the point at all. It’s much more personal to you as an individual.

It’s very personal, and it’s the very opposite of that.

Do you have personal criteria for choosing records to release?

I say “Does this hit me in the heart? Yes it does, therefore it’s good, hopefully it hits somebody else in the heart too. Does this not hit me in the heart? No, next song.“ My editing is based on that and the way I pick material and everything about the label is based on that relationship. It’s created a lot of controversy over our label because there’s a lot of relationships I make between music on comps that my seem arbitrary and sloppy and lame to people, but the truth is that’s for whatever reason what hit me in a spiritual way or in an emotional way.

Even my record collection at home I’ve curated to that point where I don’t want to have a record in my house – even if I think it’s interesting or cool music – if I don’t feel like I could sit down with the person in it and enjoy a beer, then I don’t want their record in my house either because I take that shit personally. So that’s sort of my approach to curating. If I have any curatorial limit it’s that I won’t listen to music by people I don’t think I’d like personally.

In what sense do you mean controversial?

More academically orientated people, or people who feel like they’re the guardians of culture or whatever, they’ll say the same about me and Sublime Frequencies that we’re just punks who are into exoticism or strangeness or maybe we’re just into finding the most obscure and bizarre. And well no, we are just obscure and bizarre people (at least to compared to the squares who are prone to criticise us on this level) and these are the things that happen to relate to us and that haven’t been put out before but we feel should be available.

Is there a long term aim for the label beyond just checking off more and more from your growing list?

I wish I knew. I’ve been struggling with that I don’t have an endgame plan. This tour was the first time I’ve broken radio silence of talking about the label and stuff. I thought that talking to reporters would help me crystalize my ideas a little, but instead it’s just made it more confused and muddled and psychedelic so everything’s got really undefined.

Do you enjoy talking about the label?

No, I haven’t really found a way of finding great joy in sharing this information because the records are a better messenger for my ideas than anything I could say and a lot of times when you talk about stuff it just loses a lot of its power. You tend to take away from the mystique and the personal relationships that people form where their imagination meets the work and suddenly there’s this guy who is telling you how he intends for you to experience it and it can really devalue a lot of the work and make a big thing a lot smaller.

That said, the label does seem to be contextualizing its releases more than before. Do you have other personal effects, photos and documents from the artists you release?

These days more and more of our records come with liner notes. I’m actually sitting on a 400-page autobiography of Abner Jay that’s never been printed. The thing is I don’t own anything, I just borrow from people and have access to things. Actually if you look at my holdings as an archive it’s pretty pathetic. Even when I finish a project, if I’m using records to transfer from I always sell them right afterwards, or if I use a piece of art on a record I sell the piece of art. I don’t keep anything. My archive is pathetic.

Check out the Mississippi Records discography on Discogs and look out for new releases in all good record shops. If you’re in Portland, Oregon, you can visit them in person at 5202 N Albina Ave, Portland, OR 97217, United States.