Published on

May 22, 2015

Category

Features

Jazz pianist and artist Jason Moran has lived in Harlem for twenty two years.

While he has seen the area change dramatically in that time, to understand where modern Harlem is today you have to go back to the beginning of the 20th century. The adopted spiritual and cultural home of the black American community who made the blocks between 96th (or 110th depending if you’re east or west of 5th Avenue) and 155th street in Manhattan their own, the outpouring of concentrated creativity in the 1920s turned Harlem into a mecca for African American artists, writers and musicians.

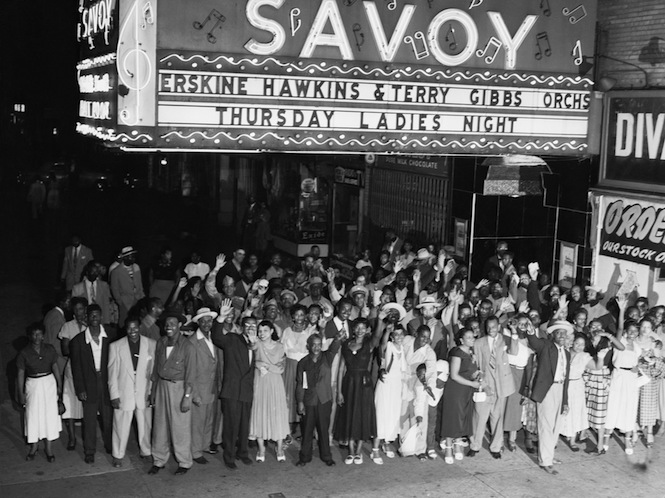

As James Baldwin and Langston Hughes were writing new histories for the community to be read by day, the era’s greatest jazz musicians made the night their own. Whether at the Cotton Club, the Savoy Ballroom or the Apollo, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and the great band leaders of the swing era made sure no-one left Harlem without a spring in their step. As their reputation grew increasing numbers of well-healed midtown New Yorkers took Duke’s advice and jumped on the proverbial A-train for a piece of the action.

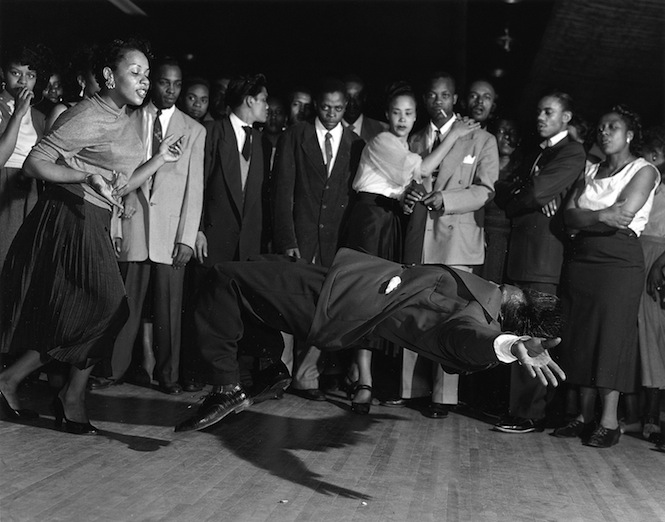

Grand spaces – the Savoy had two stages and a capacious dance floor – the clubs of the Harlem Renaissance were built for dancing, the jazz musicians consummate entertainers who expanded on the rag time and Dixieland traditions of New Orleans to make greater space within the music for solos and self-expression. The stages were brassy and the music reverberated above the breathless crowds.

However for the young musicians making their names under the likes of Cab Calloway and Count Basie, the big band solo still represented something of a restriction and the years that followed saw the complexity of the music increase in tandem with shrinking band sizes. Charlie Parker may have cut his teeth in the big bands of the mid-west but along side Dizzie Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, he was among the first to ask, in Jason Moran’s words… “What if I make these phrases move totally differently? You won’t be so easily able to swing to this song, you’ll have to concentrate a bit more. And what if the rest of the band does that as well?”

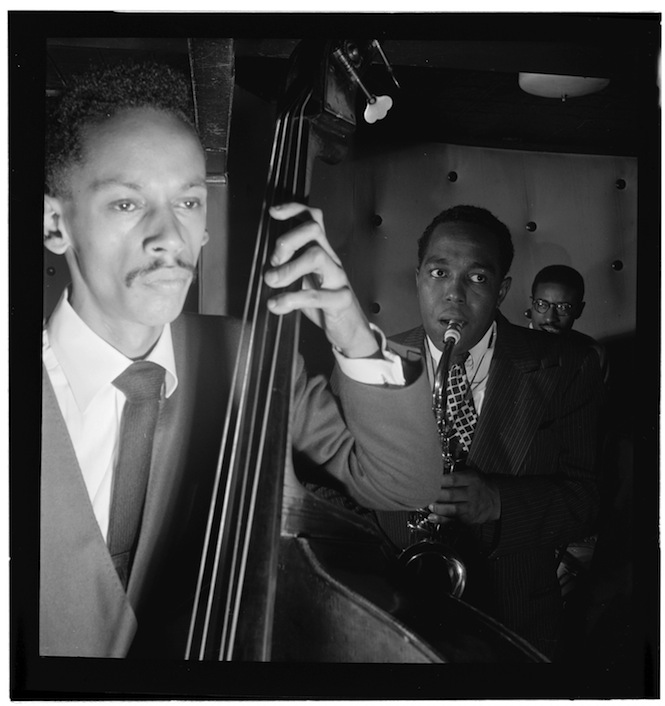

Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and band at the Three Deuces – Photo: William Gottlieb

So be-bop was born, and with it a new breed of jazz club that needed to satisfy the evolving requirements of musician and audience. Structurally complex, fiercely virtuosic and at times wilfully difficult, to get the most out of be-bop you needed space for your head more than your feet. Jazz clubs and their stages became smaller, the acoustics dampened for clarity, and the large dance floors were replaced by tables and chairs. Politically speaking, it represented a moment of greater empowerment for the musician, and elevated jazz from entertainment to art form overnight.

It was perhaps no coincidence then that the clubs that made be-bop great began pulling jazz further and further south of 125th Street. Founded on 118th Street in 1938, Minton’s Playhouse hosted legendary jam sessions throughout the forties, where Bird, Diz and Monk honed their sound. Three years earlier, the Village Vanguard opened its doors in the Greenwich Village, quickly followed by the Half Note, the Village Gate and the Five Spot, as the downtown scene flourished. The bright lights of mid town were next and it wasn’t long until jazz found a new home nestled among the art galleries of 52nd and 53rd streets. By the time Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers recorded A Night At Birdland in 1954, be-bop had taken over the city.

Photo: William Gottlieb

Among those mid-town joints was the Three Deuces. Although he managed to find people who’d been to the see Bird, Miles Davis & the rest on its padded stage, Jason Moran wasn’t able to find anyone who’d romped and stomped at the Savoy. Fascinated by the way in which the spaces not only helped form and respond to the needs of the music, but also by what these said about the black American experience in what was still a visibly divided and unequal city, he set about trying to recreate two of the most emblematic stages from these contrasting moments in jazz; the swing-era Savoy Ballroom and the be-bop-era Three Deuces.

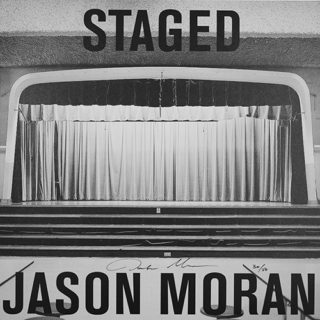

Entitled STAGED, Moran has displayed these spaces at the Venice Biennale where they will remain until November. With a number of acclaimed releases for Blue Note under his belt, Moran has also cut three new tracks to vinyl to accompany the installation, drawing a line through the jazz continuum from its earliest manifestation in blues and work songs all the way through to hip hop and sample culture.

Speaking eloquently about the way in which New York’s jazz clubs have helped define the music and the communities in which they’re rooted, Jason Moran gave us a few moments of his time to tell us a little bit more about the project and why, in an increasingly gentrifying Harlem, it’s as important as ever to consider what happened to the spaces that made it great.

Could you begin by introducing your project STAGED and what it was that interested you in these spaces?

I have these two stages, we’ve called them STAGED and they are a look at how architecture impacted the sound of jazz and the possibilities of jazz and also to examine America’s tendency to totally demolish historic sites, specifically jazz historic sites. This is an effort to raise them back up.

Generally when I’m doing that as a pianist I’m doing it from a point of view of playing the music – I’ll raise the music, but this time I’ve decided to raise the structure that was the context for the music.

So one is called the Three Deuces, which was a very famous club in the ‘40s and ‘50s on 52nd Street in NYC, which at that time was like a jazz mecca. Everybody played there. Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Max Roach, Charles Mingus, you know, every great musician of the be-bop era was on this stage.

I’m looking at the proximity, small bands in this space, big bands in the Savoy Ballroom, and looking at the scale for the music.

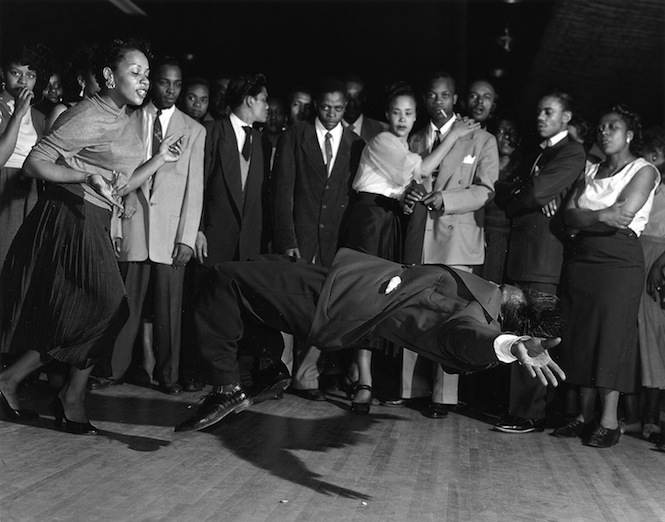

Inside the Savoy Ballroom – Photo: Associated Press

So at the Savoy, musicians were entertainers and the audience were the dancers, whereas at the Three Deuces, it was more about sitting and listening to musicians as artists.

There’s a different trend that started to happen with relationship to these two clubs which also points to how the music’s relationship to its audience shifted dramatically. People who came to the Savoy came to dance, they actually came to just party. Whereas people who came to see Charlie Parker, they also came to party, but they started to do it while sitting down. A lot of stuff changed with the protocol for listening to jazz.

But also I was really struck by the materials that were used in both of these spaces. So the Three Deuces had this way of using padded material to really put a dampener on the sound of the music, to kind of control it in a way. In the Savoy the music was open and making people fly all over the place.

So the Three Deuces throws it back on the musicians rather than the audience?

This is the thing that I’m also trying to think about it, because as a contemporary musician what I never got to experience was when jazz was a popular music. I watched hip hop be popular music or electronic dance music, but eventually that will be old like house music, or like disco. So eventually it becomes antique, but I think those are the relationships I want people to start to question. Our relationships to where we listen to music, what are the spaces around it and what do they tell us about the music we’re listening to.

You mentioned at the start about America’s tendency to rip down its significant structures. What happened to these spaces?

The Savoy Ballroom was torn down and now an apartment building is there. And that was in Harlem, in my neighbourhood. And the Three Deuces was also shut down, I think in the ‘50s and now it’s a big office building. It’s one block away from MoMa in NYC. And that’s also kinda interesting to think that whether those histories still have ways of resonating. It’s been decades and decades and generations past and I do consider what happened in these spaces, because landscape and setting are important.

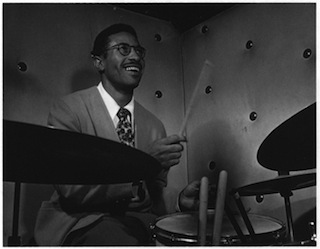

Max Roach on drums behind Charlie Parker – Photo: William Gottlieb

Was there a reason why you particularly chose these two clubs as emblematic of this?

Well there were photographs that I saw of the drummer Max Roach playing at the Three Deuces. And he’s the drummer, shoved in the corner. I mean this is one of the great political drummers as well. He’s making music like the Freedom Now Suite he’s very outspoken about racism and classism, he’s one of our leaders. And here he is, this great drummer, full of syncopation, shoved in the corner in a padded wall in this photograph.

So that struck me because generally when I look at old photographs of musicians I’m looking at the musician, like “oh that was such a great musician, but OK, so where is he?” So that’s what I started to ask myself about and that’s what made me do the Three Deuces. And the Savoy Ballroom, because I live in Harlem and I’ve been there for the past twenty-two years, I have always been thinking about where these grand spaces were, these grand spaces that were built for music and built for enjoyment that don’t really exist in Harlem anymore. So I saw the photographs – there aren’t many photographs of the Savoy Ballroom – and we started from there and raised it back up.

It has a contemporary resonance with the changing face of Harlem too, right?

Yeah, because these are cultural institutions. We don’t really think of clubs as cultural institutions but from what they provide, it’s all the conversations that happen in there and it’s all the conversations that they lead to outside of those spaces, and that is pretty powerful. We don’t generally think of entertainment that way.

You mention Max Roach – the music you’ve recorded for the STAGED record also audibly references slavery, work songs and the vocabulary of the civil rights struggle.

In jazz a lot of the music has evolved from those blues and field songs and work songs but you know it’s very subtle how it gets to where Charlie Parker is. And especially in jazz music, politics is already embedded in the fabric of the music because the music comes out of a need for oppressed people to actually play a solo, which means tell your story and say it out loud and that was not a right afforded many people at that time, because you were afraid that you’d be murdered.

The STAGED record contains pieces that are part of that. The hammers and the chains, the song ‘He Cares’. I’m trying to look at songs as you can look at fragments and those fragments when focused on can really overtake everything. That’s how that music came out.

Max Roach at the Three Deuces, 1947 (Photo: William Gottlieb). Nasheet Waits at the new Three Deuces, 2015 (Photo: The Vinyl Factory).

The solo as giving someone a voice was emblematic of the change in self-determination in the music between the golden eras of the Savoy Ballroom and the Three Deuces and then after that. Be-bop was liberation for the artist, as if it was wilfully difficult.

Right and I feel like between big band swing music all those musicians came through those swing bands, Charlie Parker came through those bands in the mid-west. But then when he emerges, then he’s like “I have a different code. This displaying so where everyone knows where the beat is and can dance to it, well what if I really make it like this, what if I make these phrases move totally different? You won’t be so easily able to swing to this song, you’ll have to concentrate a bit more. And what if the rest of the band does that as well?” Louis Armstrong alludes to that in the ‘30s, he alludes to that kind of freedom but then there was a real shift twenty years later and that’s an important notion that they make.

The Three Deuces (STAGED)- Photo: The Vinyl Factory

How did you actually go about actually recreating these stages?

I tried to source as many photos as I could from archive collections and then also try to start to talk to musicians. Nobody I knew went to the Savoy Ballroom. Many people I knew went to the Three Deuces, including the great jazz impresario George Wein. So I sent him a message saying “George, do you ever remember going to the Three Deuces?” and he said “yes” and talked about a band he saw there. And then I sent him a photograph and asked “what colour do you think that wall is?” because everything was black and white so it’s hard to determine what kind of space it could be.

So I tried to have those conversations too because it was important to hear what musicians would say about walking into spaces, so you know when you see a floor plan for the Savoy Ballroom, this grand space which actually had two stages and then a huge dancefloor and then all the places where people sat.

That was part of the process. Look at photographs, talk to people, look at photographs, talk to people. But then there was a moment when it was impossible to actually recreate the photograph. Like the fabric that’s on the Savoy Ballroom, that is not actually the fabric that they had.

The Savoy Ballroom (STAGED) – Photo: The Vinyl Factory

And there’s a musical element to both installations too?

In this space there’s a player piano that Steinway just created, this is a brand new system called the Spirio system which allows their concert artists to come and record onto the piano and that it really replicates the sound. So it’s a different kind of ghost; I never really get to hear myself play on a piano. And it plays the song ‘He Cares’ and it’s in sync with the Savoy Ballroom with the man singing ‘He Cares’ as well as all the hammers and chains from the recording of the Angola prison workers. So there’s an ambient sound coming from the Savoy Ballroom stage but the answer comes from the music that happens on the Three Deuces. So they do have a conversation. It’s not only a conversation about where the music was but it’s also a conversation about the history that preceded those spaces that still ties them together.

Jason Moran’s STAGED is out now on The Vinyl Factory in collaboration with New York gallery Luhring Augustine. Click here to order a copy.

See STAGED at the Arsenale at the Venice Biennale now until November. Click here for more details.