Published on

March 14, 2017

Category

Features

If jazz has Sun Ra and funk has George Clinton, then reggae has Lee “Scratch” Perry.

There’s a Trimurti of artists who straddle the same fence between genius and insanity, firmly rooted in their respective genres, yet their personas and catalogues shatter expectations of what a recording artist should be.

Jazz had Sun Ra with his elongated big-band experiments, capes of plumage and Afro-cosmic prose. Funk was gifted George Clinton with his acid-fuelled family jams, luminous dreadlocks and a penchant for wearing nappies on stage. And reggae, a genre replete with innumerable nutcases, has Lee “Scratch” Perry flying the flag for laissez-faire eccentricity at the ripe old age of 80.

Perry may seem at first glance to exist outside of the traditions and restrictions of reggae – his fractured dub-scapes, peppered with animal noises and freeform gibberish, will strike the casual Bob Marley listener as entirely alien – but much like his funk and jazz counterparts, he’s a man steeped in tradition.

Like Ra starting his career tinkling the ivories on Chicago’s trad-jazz circuit, and Clinton’s doo-wop pre-history, Perry found himself in the thick of reggae’s roots at the turn of the ’60s, working for pioneer Coxsone Dodd just as Jamaica’s love of U.S. R&B morphed into ska and their own upside down take on the style. In the following decades he sat at the forefront of most major evolutionary points, from rocksteady, through reggae, into dub and beyond, dabbling in dancehall, punk, pop, and dubstep to name but a few pauses he’s taken along the way.

All three of these colourful characters often find themselves deified, and sadly not always for their enduring ability to repeatedly invent, and reinvent their genre, but instead for their apparent craziness or worse, zaniness. Yes, Sun Ra did claim to be from Saturn, indeed Clinton toured with his pet piglet named Officer Dibbles, and Perry of course spent some time in ’79 scrawling curious words on every inch of wall in his studio, crossing out the vowels as he went, before (allegedly) burning it down.

Whilst these stories highlight and may even explain some of the extremities of their output, in many ways it detracts from the method behind the apparent madness, because, whilst their music transcends space and time, their Earthly presence suggests they are simply men who eat, sleep and shit, just like you and I, all be it in better but perhaps less versatile garms.

Lee Perry

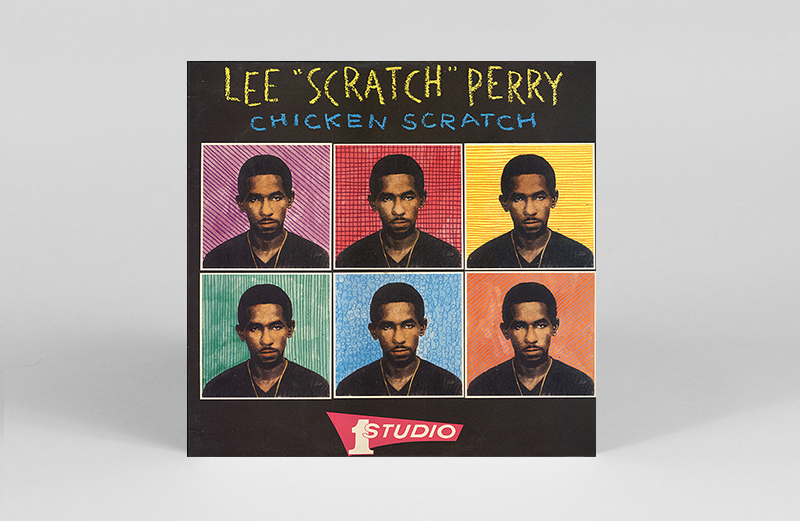

‘Chicken Scratch’ from Chicken Scratch

(Studio One, 1985)

Scratch’s nebulous music career started as a mere trickle when “Little Perry” – he was just shy of 5 foot in his early 20s – got a job sourcing records for Coxsone Dodd’s Downbeat sound. Perry eventually auditioned as a singer with a song about the dance in vogue in Jamaica at the time called the Chicken Scratch. It didn’t go down well in the studio and Perry found himself the butt of jokes that renamed him “Chicken Scratch” and eventually just “Scratch”.

Dodd recorded it anyway with a group who’d soon become The Skatalites, and cut a dub which despite working the dance, didn’t get a commercial release. I’ve got no idea if this is the original recording, I think it cropped up on a comp in the ’80s but it stands as a remarkable moment where his career could’ve been still-born, and steered into the skid of a callous nickname which wound up serving him well for the next 5 decades.

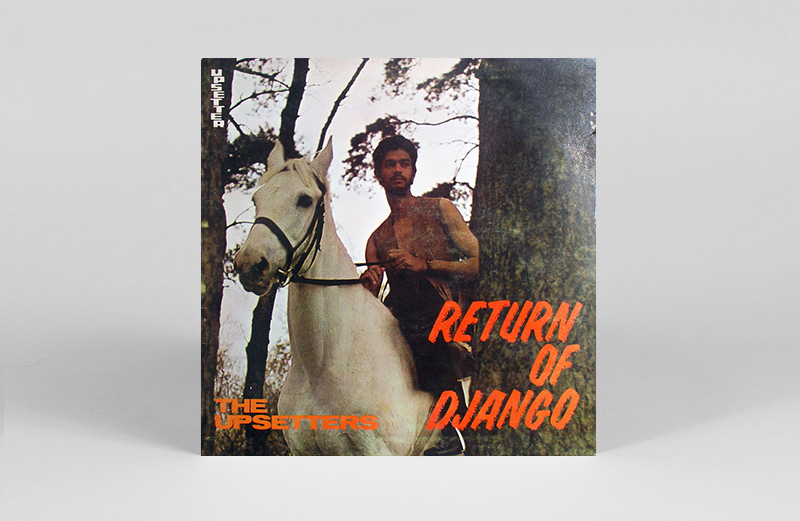

The Upsetters

‘Return Of Django’ from Return Of Django

(Upsetter, 1969)

Largely derided for his fragile and limited vocal range, Perry soon turned his hand to production, working with an ever changing array of Jamaican musicians he dubbed The Upsetters. The first incarnation of the group recorded ‘Return Of Django’ in ’69 which soon went Top 10 in the UK after its use in a Terry Gilliam directed Cadbury’s commercial.

It also highlights Jamaica’s obsession with the spaghetti western at the time, specifically Django, the only spaghetti western truly worthy of anyone’s time; the tale of a monosyllabic drifter who saunters into town with a coffin before brutally killing everyone that crosses him. Dead good.

Max Romeo & The Prophet

‘How Long Must We Wait’ from 7″

(Camel, 1972)

Romeo’s most notable collaboration with Perry was the politically charged sufferer sounds of War Inna Babylon featuring the evergreen ‘Chase The Devil’ but their relationship went back to the late ;60s offering many a lesser known 7″, plenty of which were fantastic.

I’ve picked ‘How Long Must We Wait’ from ’72 due to the quasi-funk elements, showing that ten years into his recording career, Perry was happy playing around with the limits of his genre. Also note Perry’s appearance as The Prophet, one of his many grand pseudonyms which also include King Scratch and God.

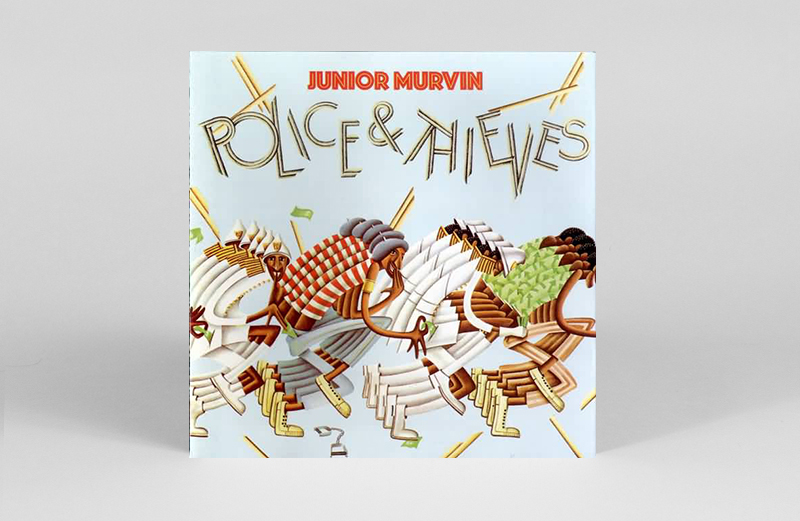

Junior Murvin

‘Police & Thieves’ from Police & Thieves

(Island Records, 1977)

With his “crazy” dub(ish) sets in the ’70s like Super-Ape and Kung-fu Meets The Dragon, it’s easy to forget that Perry was a master when it came to crafting a pop song. ‘Return Of Django’ had caught the ear of the great unwashed British public in ’69, and his work would return to the hallowed halls of Top Of the Pops a few more times with the likes of Susan Cadogan’s ‘Hurt So Good’ and Junior Murvin’s ‘Police & Thieves’.

On release in ’76, ‘Police & Thieves’ became an underground success, inadvertently soundtracking the Notting Hill Carnival which erupted into riots that year, no doubt leading The Clash to rework it for their debut album in ’77, an act which Murvin later lamented, claiming “they have destroyed Jah work.” None the less it probably helped propel the original into the UK Top 30 on its re-release in 1980, and for me remains the greatest (only?) pop hit to feature reggae’s thing for almost earsplitting hi-hats.

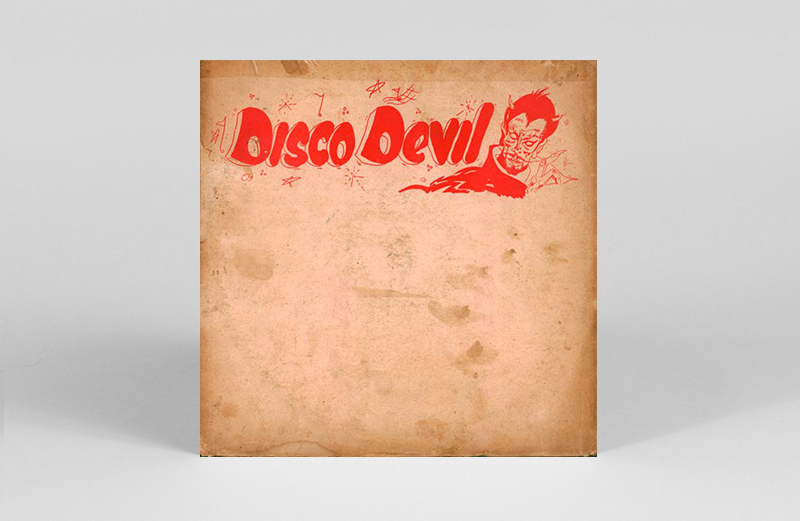

Lee Perry & The Full Experiences

‘Disco Devil’ from 12″

(Upsetter, 1977)

The Prodigy’s wholesale lifting of the hook from Max Romeo’s ‘Chase The Devil’ means it’s a top drawer selection when playing reggae to non-reggae crowds but despite how much I love the record, believe me it gets tired sometimes. Cue Perry’s retake of the track, handily featuring said hook, as if in ’77 he had some clairvoyant foresight that it would become one of the most familiar lines from his back catalogue.

‘Disco Devil’ finds Perry both on the mic and behind the faders, showing off that razor’s edge of “is he, isn’t he?” dub madness, and remans one of my favourite moments from his career.

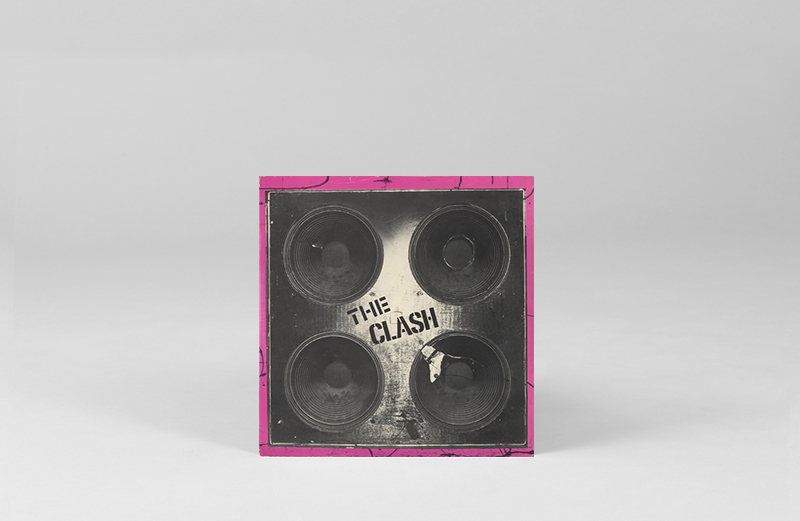

The Clash

‘Complete Control’ from 7″

(CBS, 1977)

Convoluted legend surrounds this record. Perry’s been quoted with his disdain for The Clash’s version of ‘Police & Thieves’ yet others say he loved it and jumped at the chance to produce this single whilst he was in the UK in ’77. Supposedly the original mix was echo heavy and deemed not radio-worthy, so we’re sadly spared a true early marriage of a dub-maestro tweaking a punk-rocker but it’s still an interesting excursion even if Perry’s presence was mostly mixed out of the final version.

Years later, a Perry-produced version of ‘Pressure Drop’ surfaced, presumably from the same recording session, which might suggest more input from Scratch. Whether he really had much say in what they were playing is lost in the annals of time though; apparently he still thinks he was working with the Sex Pistols.

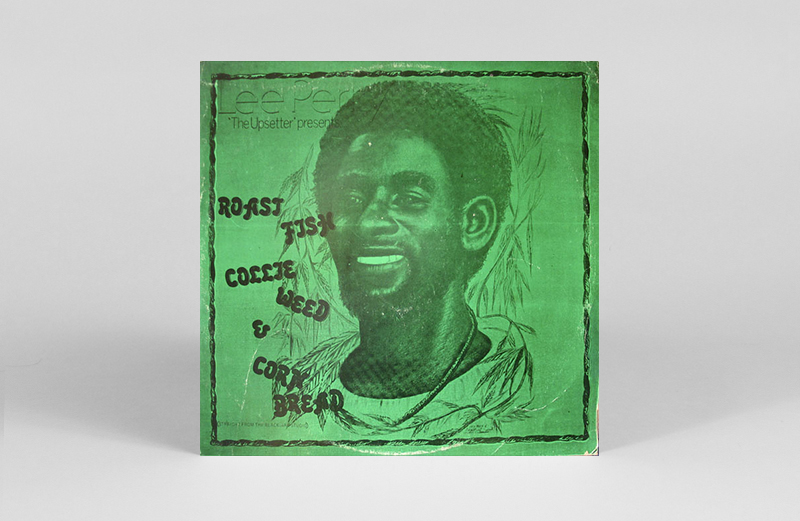

Lee Scratch Perry

‘Roast Fish & Corn Bread’ from Roast Fish, Collie Weed, & Corn Bread

(Upsetter, 1978)

In the years leading up to the Black Ark studio fire, Perry’s behaviour became more noticeably erratic, and much of his late ’70s output reflects this. Psychedelic dub freakouts, the aforementioned gibberish chatting, and on this wonderful occasion, a cow, or more likely, Perry doing an impression of a cow. This is the man at his most curious, most playful, and quite possibly most stoned.

Keith “Daddy Kool” Stone once told me he was drawn to dub and roots because he came from a psych-rock background, so the mix of strong rum, good weed and heavy FX-drenched bass appealed instantly, and though I’m one of those annoying t-total types, listening to this record, I can hear exactly what he meant.

Bob Marley

‘Rainbow Country’ from 12″

(Daddy Kool, 1979)

In the run up to mega-stardom via Island Records, Bob Marley worked with Perry on a brace of great albums for Trojan – Soul Rebels and Soul Revolution pt 2 – and their collaborations would continue sporadically through the’ 70s with standouts like ‘Punky Reggae Party’ in ’77 and this metallic beauty.

It was recorded around the Natty Dread session in ’74 using what I’d guess is the infamous “first drum machine in Jamaica” the EKO CompuRhythm which Perry also experimented with on a previously unreleased dubplate called ‘Chim Cherie’. ‘Chim Cherie’ would later serve as the backbone for Shinehead’s iconic take on ‘Billie Jean’.

The Terrorists & Lee Perry

‘Guerrilla Priest’ from Love Is Better Now 12″

(Splif Records Ltd., 1981)

In the wake of the Black Ark fire, Perry disbanded The Upsetters, uprooted and spent the next few years trodding the globe. Starting in New York, he stumbled upon a group of reggae obsessives who’d been haunting the NYC underground, playing well crafted reimagining of Jamaican tracks on the punk circuit, opening for the likes of no-wave elders Suicide, SF’s synth-punk pioneers The Units, and Lester Bang’s Birdland. Along with The Offs, they made a one off and skanky appearance on the Max’s Kansas City label before teaming up with Perry for a brief stint as his backing band, and recording the largely overlooked ‘Guerilla Priest’ with Scratch on the mic riding a smooth rework of the ‘Tonight’ rhythm.

Perry’s ties with the punkier end of dub would continue into the ’80s having landed back in England and listed the help of post-rock pioneers Dif-Juz who backed him for a brief stint before winding up in the studio where they worked on a Perry produced mini-album which remains to this day in the 4AD archives, unheard by pretty much everyone. It’s claimed that Dif Juz disliked the results of the session (there’s a theme here perhaps) but band leader Dave Curtis later claimed “it’s the best thing Dif Juz ever did.” If anyone from 4AD happens to be reading, please release it, or at least let this Spiky Dread fanatic have a listen!

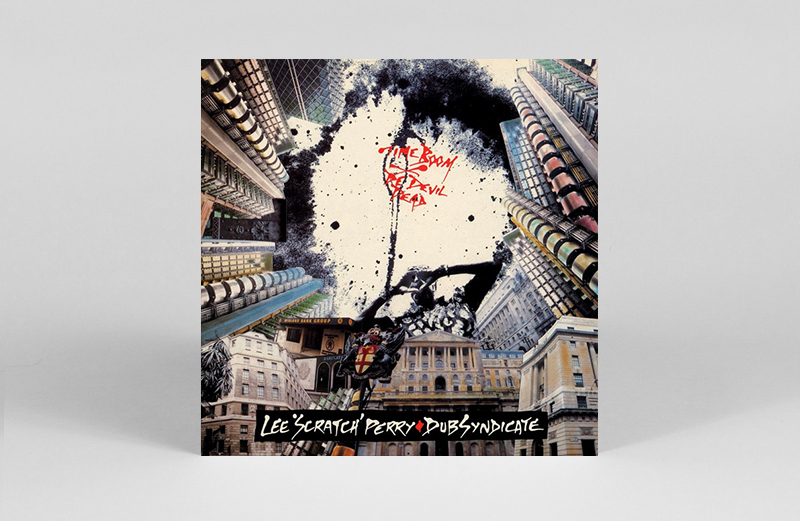

Lee Scratch Perry & Dub Syndicate

‘Night Train’ from Time Boom X De Devil Dead

(On-U Sound, 1987)

I’m cheating a little on this final selection because as much as I think it’s important to mention Perry’s relationship with our own dub-master Adrian Sherwood, I never really dug their work together. It’s decent but there’s far more interesting material from the On-U camp which is worthy of your time. However this album outtake featuring Perry gracing an earlier tune by On-U mainstays Dub Syndicate is a sparse and echo-drenched marriage of icy ’80s electronics and the rattling bones of hand-percussion and shakers.

Elsewhere in the ’80s, you can find Perry dabbling wholesale in electro on ‘Funky Joe’ and working hand-in-hand with his south London dub counterpart Mad Professor on albums like Mystic Warrior.

Further increasingly digital experiments continued through the ’90s, many worth a listen but there’s a hell of a lot to sift through, so I’ll leave you instead with this slightly uncomfortable hit from his 2008 album Repentance which surprisingly features party expert Andrew WK on production duties, leaving Perry to wax lyrical about looking for a pum pum for his kitty in New York City.