Published on

August 14, 2014

Category

Features

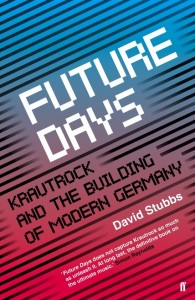

We caught up with music critic and author of a new definitive history of krautrock David Stubbs to find out more about one of the most defining eras in modern music.

There’s a paradox at the heart of the music first disingenuously and now somewhat more affectionately known as krautrock. Although it was, as David Stubbs explains, a ‘posthumous music’, categorised as such long after the moment had passed, bands like Kraftwerk, Can and Neu! couldn’t have been more self-conscious in their attempts to redraw a sense of German cultural identity.

Their rejection of over-cooked Anglo-American rock forms was wilful and would have been controversial in Germany, had any one really been paying attention. As it was, their rehabilitation of what it meant to be German in post-war Europe began abroad, a cultural export that marked a radical rupture from the lederhosen glad glibness of Schlager and the false claims any German artists had on the ‘blues’, a music and a sense of being about as foreign to the German sensibility as autobahns would have been in the Mississippi delta.

Perhaps more than almost any other music, krautrock defines and is defined by its context. Beginning with the term itself, music writer David Stubbs has sought to do just that, placing what Simon Reynolds calls “the ultimate music” in a historical and cultural context in order to understand how bands as stylistically disparate as Cluster and Faust came to be caught in the same net.

Considering that it was abroad where bands like Can and Kraftwerk made the biggest impact, it was fitting that we met David in a French cafe over an English tea to explore the conceptual and historical framework of the genre as explored in his new Faber-published book Future Days: Krautrock And The Building Of Modern Germany.

You can listen to David’s krautrock Spotify playlist as you read and scroll down to see his pick of the five most important tracks and the records where you can find them.

What were your first encounters with the music and what appealed to you first time around?

I suppose I started listening to a lot of that kind of music in the late 70’s and I do talk [in the book] about actually being a bit of a football fan. They used to have these air horns and that was one of the first things that made Europe seem exotic to me as I never got to travel there. And I think that sort of ignited the initial fascination, so that when I started hearing all these records – and a lot of them do include a lot of abstract electronic noise – I did sort of make the connection.

I was always interested in the extremes, Sun Ra was one, Stockhausen another and then there were groups like Can and Faust, whose music was just being reissued at that point. I was just absolutely fascinated and staggered. I am one of these people who tends not to be a songs person; I like form, I tend towards the avant-garde and I am fascinated by people who reconfigure the way this kind of music sounds.

Given that it is, as you say, on the more extreme side of things, it’s remarkable that it continues to be so revered among so many different contemporary scenes.

I think one of the things that interests me about krautrock is that it’s sort of a posthumous music. It only really started being taken really seriously as a collective phenomenon by the time it had petered out.

And I think it’s gone through renaissance after renaissance. It went through one in the late 70’s and early 80’s when a lot of the punk and post-punk people were all krautrock heads – Jim Kerr, Mark E Smith, John Lydon – all these people were all into the music. Then there was a second wave in the late 80’s with people like Loop and then Sonic Youth and then of course there was the whole 90’s thing with Stereolab.

In the introduction you also attempt to define what is meant by “krautrock” and where the term came from. Musically and stylistically speaking what we understand as krautrock is actually incredibly disparate.

It was the first thing I had to address in the book was this question. These days however I think the word has become cleansed, because people don’t use the word ‘kraut’ anymore. People of this generation coming up now don’t think that Germany or the Germans are in any way a residual issue as they were three or four decades ago.

It still wrankles with those artists and it’s very difficult because you’re on the phone to John Weinzierl of Amon Düül and you say ‘I’m writing a book about kr…’, because they find it a deeply insulting term.

It’s less of a genre and more a description of an era from the outside that seemed somehow alien and no-one could really get a proper handle on.

Exactly, for me what I tried to establish is that there are common properties to these disparate bands, there are things they have in common, for instance: innovation and the rejection of Anglo-American models of making pop and rock music. Part of that means no choruses, rather a more spatially linear approach and with less of a stress on vocals and the idea of a front and centre vocalist. They tend to be more sonically collective. You look at Can and drummer Jaki Liebezeit said ‘No Führers’, or ‘no leaders’. I think they almost made that connection that people who went up on stage to receive the adulation of a mass audience actually had dodgy and negative connotations.

And as an ethos, this collective idea connects the more pastoral, mystical elements of the movement with the functional, urban, electronic style.

It’s true, there’s a sort of primitive futurist feel to it; on the one side it’s going back to the fields and on the other hand its very futuristic – any time but the present.

I think Kraftwerk were interesting in that sense. They were not just purely futurist, Kraftwerk were as much about the past as about the future. They were about reconnecting with these great German traditions like Bauhaus and there are huge comparisons between the Bauhaus movement and what Kraftwerk were doing.

And the fact that we’re talking about this suggests that putting this music in its proper historical context is perhaps more important than with almost any other genre. Is it possible to listen to krautrock without knowing that it was this very self-conscious rupture and re-appropriation of German creative identity following the Second World War?

I think you could just listen to it and be immersed in the trippiness of it, but I do think it’s important. What I find is that so many people don’t really know the first thing about it – it’s one of these terms that’s dropped quite a lot. Surprisingly, aware and engaged and intelligent people don’t really know where to begin beyond Kraftwerk, so I do think it’s important to demystify it.

Given that it’s been grouped as a movement retrospectively. What kind of audience would this have had at the time?

Well I think it varies. I think people like Can were able to get fairly respectable audiences but in terms of being taken seriously, the first place was France, then England and then perhaps America before it became sort of a worldwide thing. The French were the first people to take it seriously, certainly not the Germans themeleves who have always been fairly skeptical. I know a lot of the bands would go off to places like Bolivia on tour and find that people knew the records and then come back to their home towns in Germany and no-one would recognize them.

So the market for these records was also abroad?

For us there’s this whole idea of the Teutonic other and Kraftwerk for example traded on that idea of the Teutonic other and how amusing people might find their Germanness, but if you’re German there’s a whole dimension there that doesn’t mean anything.

That said, did it not help rehabilitate Germany’s own sense of identity?

This move to reject Anglo-American music was a real imperative, it wasn’t just to be inventive, because musically it was almost like an occupying force. A sense of this not being our music and so it was important therefore that innovation just became an imperative.

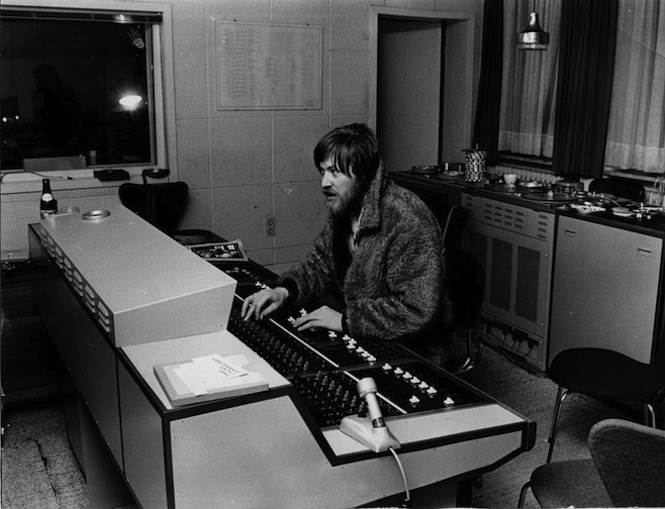

For example Conny Plank really felt that, which is why he was constantly willing to offer his services to a whole range of musicians and give them studio time to enable them to really make the best that they could.

And in the 60’s in Germany you really only had two choices; you had the American stuff that you were hearing over here too and you had schlager, which were essentially drinking songs that carried on as if the Third Reich never happened, but with which there were eerie comparisons. Traditional Germanic values with the whole Nazi thing airbrushed out completely.

The title of the book touches on the ‘building of modern Germany’ – what was it that krautrock contributed to that process and what has been its legacy?

The thing is, I think krautrock is the manifestation of the German capacity for cultural regeneration, which itself occurred in all sorts of ways across cinema and the arts and beyond. I think it’s the same sort of energy and humility to reconstruct and to start from scratch much as Germany itself had to do, and to come up with something that reflects favourably. You look at Brit pop for example – compare and contrast krautrock and Britpop – and Brit Pop is this rather conservative, empty, triumphalist thing, and you think of how much more of its influence krautrock is yet to realize.

Was it also a catalyst for changing the more prejudiced attitudes towards Germany in the UK?

Yeah, and I think the person I credit really changing attitudes is David Bowie and his Berlin phase. He was by no means the first but when he decided to relocate from America to Berlin, he was almost saying that the new Europe is upon us. The whole American rock thing just felt so spent and strung out and going nowhere.

When Kraftwerk were first featured in NME, the spread in the middle was a kind of photo impression of the Nuremberg rally. But post-Bowie and coinciding with those post-punk years, suddenly Germanic became the new cool, and there was an aura of cool emanating from anything from Europe but Germany in particular.

And going back to football again, I think commentators are behind the times when they keep talking about ‘ruthless efficiency’. Every time Germany were playing really well and highly effectively at the World Cup it was all part of their Teutonic efficiency and their cold-heartedness in front of goal. I think fans don’t think like that any more. It’s not Piers Morgan and 1996, this generation don’t think in those terms.

And interestingly the same terms are used to describe the football as they are the music… It’s technical, mechanized etc

Especially back then. And I think Kraftwerk were brilliant, because they were very conscious of it and played up to it all the time and were genuinely ahead of their time in that respect.

David Stubbs’ 5 era-defining krautrock tracks and the records where you can find them:

‘Hallo Gallo’

From Neu!

Neu

(Brain, 1972)

Sometimes people mistake krautrock for simply the 4/4 beat, which is only one aspect, but for that you obviously have to have ‘Hallo Gallo’.

‘Future Days’

From Future Days

Can

(United Artists Records, 1973)

You’d need something by Can, the problem is you’d have to make a choice between Malcolm Moody Can and Damo Suzuki Can, but I would probably go for something like ‘Future Days’ because that’s when they take to the air and find a way of playing in which nobody is soloing, they are just creating a weightless organic feel.

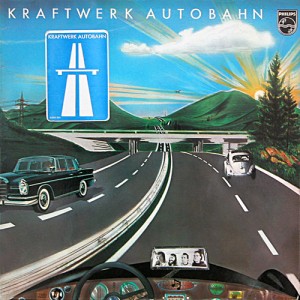

‘Autobahn’

From Autobahn

Kraftwerk

(Phillips, 1974)

Autobahn, although it’s obvious, is such a huge record. It’s almost like a culmination, and if you listen to their early albums, although they’re very different from the Kraftwerk that most people know today you can see how they’re gradually honing and moving towards that. And in a sense ‘Autobahn’ is like this metalist construction that is built on all this previous activity.

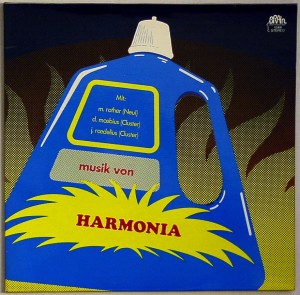

‘Sehr Kosmisch’

From Musik Von Harmonia

Harmonia

(Brain, 1974)

I suppose you might have something like Harmonia ‘Sehr Kosmisch’ that would be a good intro to that Kosmische side of things.

‘Why Don’t You Eat Carrots’

From Faust

Faust

(Polydor, 1971)

I would also have something by Faust because I think that Faust are one of the under-sung bands, and I think you could go straight into ‘Why Don’t You Eat Carrots’ because that shows their almost Dadaist way of working, all these elements collaged together.

Future Days: Krautrock And The Building of Modern Germany is out now via Faber Books.