Published on

June 28, 2016

Category

Features

Restricted, repressed and even imprisoned, black jazz musicians in ’70s and ’80s South Africa were forced underground.

But they were never silenced. In a political and social climate where playing and listening to jazz was a form of political resistance, every record became a document of struggle and a statement of freedom.

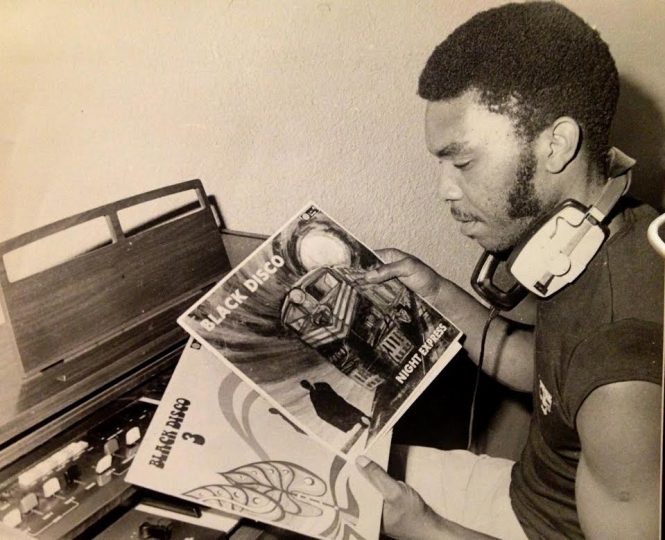

One of those records was Black Disco’s Night Express, which was released in 1976, the same year that the regime began to turn the screw. Part Philly-soul, part Cape jazz, it won instant acclaim in South Africa’s townships, who found hope and defiance in its stirring, free-flowing groove. The feeling was reciprocal. As band leader Pops Mohamed said: “It was our way of saying we are with you”.

Reissued by Matsuli Music – the independent label dedicated to resurrecting the best in jazz and soul from the nation’s under-represented musicians – label boss Matthew Temple describes the largely untold story of how South Africa’s repressed communities found a social identity in the music of resistance.

The Brother Moves On will perform the songbooks of Batsumi and Malombo at Church of Sound in London on 26th May. Click here for tickets and more info.

![]()

For those people not so familiar with the chronology, could you start us off with a bit of historical context. How long did it take to become clear that Apartheid would have a restricting effect on music in SA?

Apartheid gathered increasing momentum during the 1960s and 1970s. Until the severe repression and military government of PW Botha in the late 1970s and 1980s there were still some, albeit limited, opportunities for musicians. The severe repression followed the Soweto uprisings in 1976 and resulted in the closure of a number of music venues and very limited independent music production.The impact of colonial administration and then formalised Apartheid post-1948 has always had an impact on music, although not always restrictive. Commentators often point to music created during these times as being resilient and rich. So there were less opportunities to perform, play, record and/or be broadcast unless you accepted the role set out for you by the Apartheid government.

What kind of restrictions did they set on musicians?

The Apartheid programme was centred around denying black South Africans the right to live in urban areas, and to segregate according along so-called tribal or language groupings. The national broadcaster had separate channels for each of these language groupings. The artist Babsy Mlangeni and others were discouraged from using multiple languages on single albums and were forced to record single language albums.

The introduction of TV in 1976, and so-called “independent” homelands of Transkei, Bophutatswana and others provided new but limited opportunities for performance. In the recording industry there were only a handful of independent producers and labels – such as As-shams (The Sun) run by Rashid Vally, 3rd Ear run by David Marks, Shifty run by Lloyd Ross and a few others.

The major labels employed black music scouts and producers who were tasked with generating musical product that would sell in the townships. But for jazz musicians and others who rejected the confines of Apartheid conformity the choices were few and far between.

So both the form and the content of the music constituted a kind of resistance?

Choosing to simply be a musician or to play jazz under Apartheid can be read as a political statement. Jazz was seen as a proudly black articulation of identity with, at its heat, the idea of being free. In many ways this was construed as revolutionary. The fight was about being someone the government didn’t want you to be, as they tried to straightjacket people into fixed identities and destinies and roles within their social engineering project. But the music itself is profoundly transcendental and therein lies its power.

As jazz came to represent a form of resistance to the ideology of Apartheid so it became more and more difficult for players to find record companies that would record and issue their records, or even to find venues that could afford to keep booking these artists. Choosing to play jazz under Apartheid was not a smart financial move but many felt they had no choice at all but to play.

The impact of the black consciousness movement in the early and mid-seventies saw many groups like the Dashiki Poets, Malombo and Batsumi articulate a strong black and proudly African identity but, post the Soweto uprisings in 1976, the political struggle was turned up a notch with a military led government seeking ultimate control over the country.

As the armed resistance of the ANC and other groups increased, so the political leadership of the opposition grouped closer to the ANC. Under these conditions all artists were expected to use everything at their disposal to fight against the system. A popular slogan at the time was: “The struggle for jazz, jazz for the struggle”. There were innumerable debates on whether art could be reduced to a tool of the struggle or whether it transcended such functional interpretations.

There was also the use of allegory – Chicco’s hit song ‘We Miss You Manelo’ was of course a reference to Mandela. And there are many many more examples of musicians sending messages in an oblique manner.

Did artists suffer repression as a result of these messages, oblique or otherwise?

Musicians were arrested, harassed and sometimes imprisoned for minor offences. Often it was the musicians’ associated activities in support of the outlawed African National Congress that led to harsh consequences. Vuyisile Mini, often regarded as the father of protest song in South Africa, and composer of ‘Ndodemnyama we Verwoerd’ (‘Watch Out Verwoerd’) with words “Watch out Verwoerd, here comes the black man, your days are over”, was actively involved with the ANC and recruited into its military wing. He was arrested in 1963 and was sentenced to death. Another example is the case of reggae band Splash’s lead singer who was jailed for five years in 1983 for shouting Viva ANC at an open air concert.

Did their message get through to the people? Is it possible to discern the social impact these artists had on people?

Due to the extreme control on the radio and TV broadcast networks there were very few avenues through which overtly political music could be heard aside from small independent clubs. The use of hidden messages or songs with double meanings became a method by which artists were able to express their political views. With the lack of access to major record labels there were few opportunities for listeners to show their solidarity with political musicians. Jazz remained resilient and as I have said the act of playing jazz, or even listening to it signified something transcendental about your attitude and approach to living in South Africa.

I’m not sure that many artists saw their music as fulfilling the role of propaganda or needing to convince their audiences of a particular political position. Music fulfilled a much wider role – in providing relief from daily hardship, in expressing an identity free of every-day Apartheid constrictions and providing a sense of community beyond Apartheid defined boundaries. Having said that the ANC did broadcast on short-wave into South Africa and its broadcasts were listened to by many people aligned to the resistance. People living under the oppression of Apartheid did not need convincing of how hard their lives were and what the solutions to their problems might be, and in the most part musicians respected that.

Pops Mohamed with original copies of Night Express

Musically, who were these artists drawing on? Were foreign records available?

The reference points were clearly black American jazz from the likes of Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Miles Davis and others. But it was rooted in South African traditions. Western records were available in record stores as well as from the many visiting sailors who docked in the ports of Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and Durban.

How does Matsuli fit into all this?

We’ve been going since 2001 when we put out our first release – Dick Khoza’s Chapita. We have worked with Rashid Vally who ran the famous As-shams label, Sathima Bea Benjamin, Batsumi, Tete Mbambisa and other artists directly on licensing deals. Our mission is to bring back into print some of these long lost and neglected classics that were originally printed in short-runs with little or no promotion at the time.

Are these records now hard to come by? If so, how do you begin to track them down?

Absolutely. And even harder now as a new generation of crate diggers start to look for music from this golden period. Our re-issues have undoubtably increased the prices for original copies. Tracking them down is not the biggest issue – rather it is the licensing via the correct owners that is the biggest nightmare. Some ownership issues have prevented us from reissuing material that is still criminally out of print. In the case of the Ndikho Xaba LP we had to track down collectors to find a mint copy in order to do a transfer and audio restoration. On most of the As-shams material we are lucky enough to have access to the original masters.

Does this interest come from within South Africa now too?

Yes. There is a strongly resurgent vinyl scene in South Africa and our sales continue to increase into that market taking up at least 20% of our worldwide sales.

Black Disco Night Express is available now on Matsuli Music. Click here to order your copy.