Published on

January 31, 2017

Category

Features

Trying to categorise Annie Anxiety aka Little Annie is a futile task. This New York City musical maverick has been involved in so many scenes, but exudes a magnetic presence on anything she’s contributed to, writes Ben Murphy.

A versatile vocalist, she got her start spitting spoken word lyrics over avant-garde no-wave scree in late 1970s NYC, forming the band Annie and the Asexuals, performing at the age of sixteen at legendary gig venue Max’s Kansas City, an early adopter of punk rock bands.

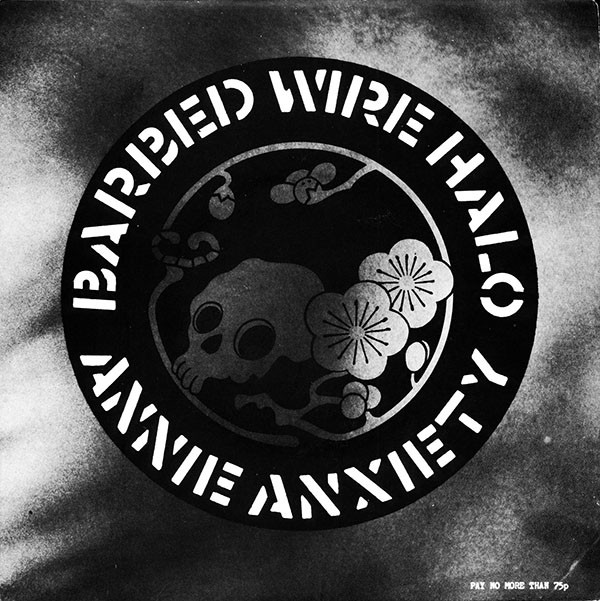

Meeting British anarchist punks Crass, she went to visit them in the UK and settled in Essex at Crass member Penny Rimbaud and Gee Vaucher’s open house/commune/ideas centre the Dial House, and ended up staying in the UK for more than a decade. Her first solo single, 1981’s ‘Barbed Wire Halo’, is an extraordinarily prescient slab of jagged electronic music, all weird samples and skeletal rhythms, Annie’s vocals entangling the sounds like ivy.

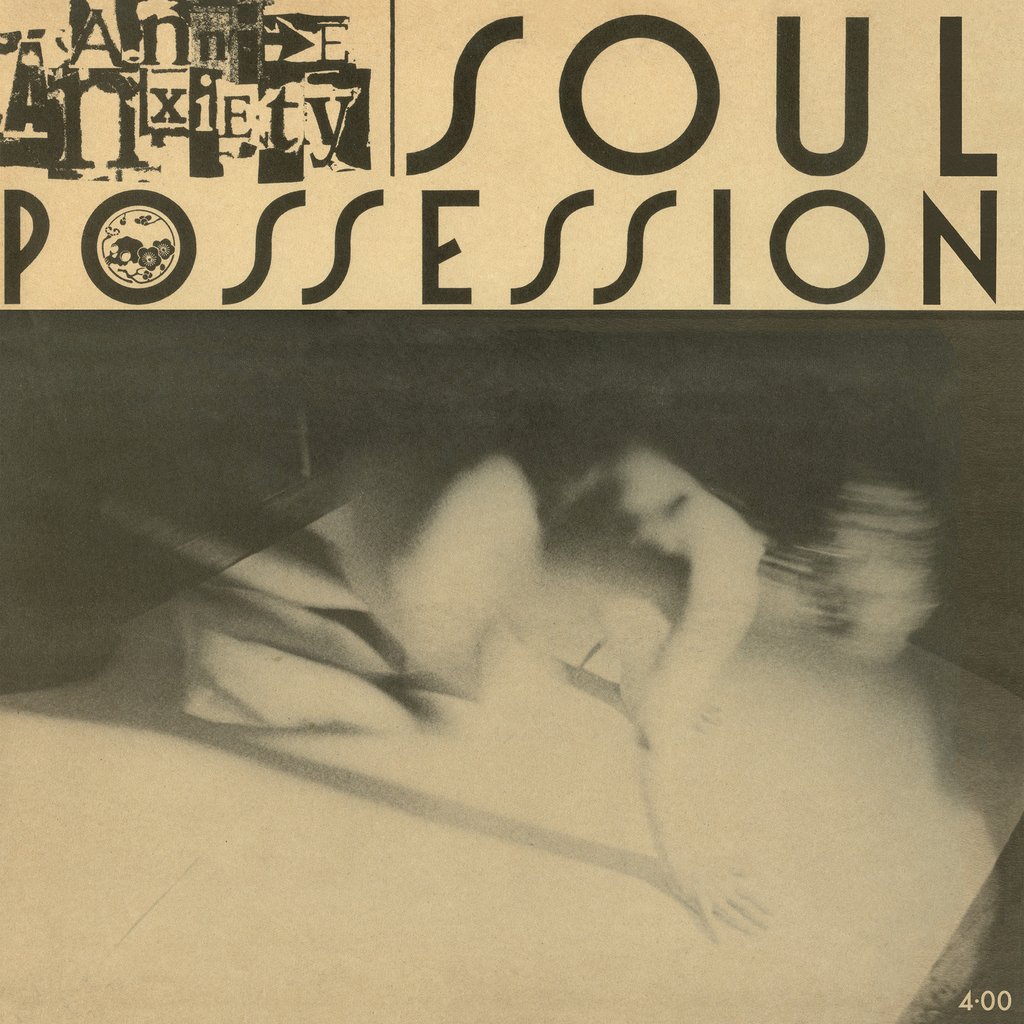

In 1984, she connected with On-U Sound’s dub master Adrian Sherwood, who produced her debut album Soul Possession – an astonishing compound of industrial, electro, dub and uncategorisable, mesmeric strangeness, enlivened by multi instrumentalist/keyboardist Kishi Yamamoto’s next-gen synths. Just reissued on Dais Records, it deserves to be recognised among the great albums of the 1980s, Annie’s haunting singing voice and dark narratives a compelling and addictive combination.

She’s worked with Bim Sherman, Coil, Current 93, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and tons more, made cosmic, avant-funk/cabaret fusions with the Sugar Hill Gang band on her follow-up record, 1987’s Jackamo, and dabbled with hip-hop and house beats on 1992’s Short and Sweet, her first as Little Annie. Ahead of some new live dates, I spoke to Annie about her remarkable musical history.

How did you get started in music?

I had no plans for anything at that time, I was so in the moment. But I had always written, drew and sung as a kid. What really happened was a fortuitous accident. I had some friends in a band called The Blessed, we were kids, we were 16, 17. They asked me if I wanted to support, so I got together with these musicians I knew from the Bronx and we did it. It was awful, but I got a taste for it. We had different people and just rotated around. We were avant-garde and just didn’t know it. We were awfully young and inexperienced too.

You played famous NY venue Max’s Kansas City at the age of 16. What was it like?

It was awful! I invited my parents down. I was living downtown, which was doable in those days, as the city was broke. There were rich people, but rich people in danger! You could live for nothing. My parents came and said it was awful, but I learnt my craft, I started doing it before I knew how, and I had to learn it as I went along.

What did you think of the early punk scene of the time? Did you identify with it, or was it not so clear-cut?

It wasn’t clear-cut. I was out the other night and someone introduced me, ‘She’s an artist, she’s a punk singer’. Punk singer, what? With the message yes, always, it was about being yourself and not being put in a box with the rank and file, but musically, I thought I was doing disco music. Which is funny now to look back and see what my idea of disco was. But I didn’t see any difference between what I was doing and what was happening in the clubs. It was rhythm-based and very percussive.

What made you move to England?

I was originally going to go to Berlin, I don’t know why. In New York, I didn’t know how people managed to survive. There was no physical means of support. I was gonna go to Berlin and I got arrested, it was a long crazy story. It could have ended really badly. I seldom say I was innocent, but I was innocent in this one. I was in the wrong place at the wrong time. I had to stay in New York till my court case was cleared away. I wanted to get the hell out. I met [English anarchist punks] Crass at that time, I was just gonna go and visit, and it didn’t turn out that way.

It was a chance for me to get educated, because it was all books, so I started reading and doing all this stuff I didn’t do ’cause I didn’t go to school [college]. We had long-winded discussions about the world and I had to look up a lot of words they were saying, but I got involved and it was interesting. Then I got into the On-U Sound thing, which was a musical education.

First you made the ‘Barbed Wire Halo’ single, which is a pretty far-out record. How did you make it? What were you inspired by musically?

Yes it is! That was me and [Crass member] Penny Rimbaud. We were setting out to make dance music, as crazy as it sounds. I listened to it recently – damn, it’s so out there. We didn’t intend it to be out there, we thought we were making a Top 40 disco record. I don’t know what happened. It was the combination of the two of us.

My father was a printer so I used to hear rhythms in the printing presses, in the subway, I loved the sound of trains, of being on trains. Different trains have different rhythms, in Europe they sound like something else. So there was that ambient sound. That was a writing tool, but I thought I was doing an anthem to connect to the people! But if we set out to make a record that strange we wouldn’t have done it. It sounds honest.

Musically it fed into the industrial sound that was coming through at the time…

Which I hadn’t heard. Afterwards I met people like [Throbbing Gristle/Psychic TV mastermind] Genesis P. Orridge and people like that, but I had no background in that sort of music. I’m pretty mundane when it comes to listening, The Bee Gees come on and I go, ‘That sounds fucking great!’ I like soul music, I like gospel. I still can’t read music and I can’t notate music. I was just following my own drummer, as corny as that sounds. Sounds in the street.

It sounds like it could have been made now…

Absolutely. It fits into what’s happening now. That’s why I love hip-hop. It uses all that stuff. Using what’s around you. Also, there’s alarm clocks and things because it’s what we had. We used whatever we could.

A few years later, you made your first solo album Soul Possession. Did you enjoy working with Adrian Sherwood and Kishi Yamamoto?

Oh God yes. To be honest I’ve loved everybody I’ve worked with, I always get something out of that. It was like I got adopted. Besides them being like family, which they still are. I sat in on every session, I did a lot of writing, learning. Kishi is phenomenally talented. The standard was so high on that musician-wise, it was fun but such an odd mixture of people, it wasn’t that Adrian set out to be odd, it’s just that’s how it happened. I loved it, I probably spent a good part of my life in the studio. You also learned to work real fast and work hard, because of constrictions. That’s what it had to be. If I couldn’t do it there were 10 other people who could do it.

So constrictions aided the creativity?

Absolutely. In a situation like that, there’s no competition, no ego. Around that talent, it’s just about the product. It’s so much about the song, and not the players. Especially in dub, it’s about what you’re not playing too and negative space. Rock guitar, that freaks me out. Stop! You don’t have to fill up every space. Less is more, and dub embraces that. It’s what’s happening in-between what you’re hearing. It was such a great opportunity. We had so much fun.

Was dub a big influence on you?

Reggae in general, I got really into it at that point. Not just reggae, but northern soul. You’d hear cuts coming from Jamaica of a Jimmy Buffett song that was horrible, but reworked you could hear it, and it was beautiful. John Denver songs, the saccharine was taken out and they became these great cuts. It got me fascinated in covering songs and reworking songs, which I love doing.

On Soul Possession you sing, but your lyrics tell stories. Is that storytelling aspect important to you?

I tell stories because I try to give things a context. I just love the audience so much I want to give the song a background. Some artists like artifice, to make it a magic show. I’m too clumsy for that so I like to bring the audience along with me to show them what the process is that got me to that. Because it’s about them, it’s always about the audience.

I do like narratives in songs, I always have, and also I’m fascinated by these stories that aren’t mine. A lot of the songs aren’t necessarily my own experience thank God, I’m just bearing witness.

You changed your name to Little Annie for Short and Sweet on On-U Sound. This record has house and hip-hop influences, as well as dub. Were these the kinds of sounds you were listening to then?

Oh yeah. Even earlier. Adrian brought back the Sugarhill Gang, Keith LeBlanc, Doug Wimbish and Skip McDonald for Jackamo. Doug and Skip played on Short and Sweet. ‘The Message’, like everybody else, it blew me away. Then Public Enemy. It was like, ‘Wow, this is fresh’. When rap, hip-hop came in, it was, ‘Thank you, we need this’. Especially in the context of what was going on, with Thatcher destroying the country. Rock ‘n’ roll stuck its tongue in your ear, as Adrian would say, and it’s just like, ‘Fuck off!’ I’m not dissing rock ‘n’ roll, that’s a very big thing to dis, but when I heard rap, it was saying let’s be a bit fucking real. There’s nothing more refreshing than the truth, even when the truth sucks.

You’ve worked with lots of other artists, from Coil to Bim Sherman and Current 93. Who’s been your favourite to collaborate with?

It’s like having a favourite brother or sister. They’re all very different, that’s always been my criteria. I was asked to do some really wonderful things. It’s a leap of faith. It’s not yours, so you have to leave your ego at home, which is always a good thing. They’re all equally valid ’cause they’re all so vastly different. The thing is, as I’m not a musician, I don’t play, only bits and pieces, I’m not a master of anything. I’ve been dependent on collaborations. That’s why, when I’m working with somebody, I try to give them equal billing. Any singer that thinks it’s all about them, see what it’s like when they’re not there.

What are you working on at the moment?

Right now I’ve just had a book of art stuff published. Then I’m going on tour with Swans. I just did some spoken word stuff, and I’ve had a lot on my mind with what humanity’s dealing with right now, but it’s changing every five seconds. I’ve also been working with a video maker here in New York, doing live vocal recording with imagery. It’s an experiment. I’ve been getting experimental again. There are times when artists have to be ourselves louder than ever, ’cause that’s what’s getting stamped on.